Chelsea is a thriving Manhattan neighborhood, regarded as the largest-ever arts scene. The district boasts over 300 galleries in its roughly 20 block area.

Chelsea developed as the haven for artists fleeing SoHo after 1995. The reasons for this move are more complex than what is seen at face value. Artists are commonly agents of gentrification, and as the SoHo arts district revitalized, rent began to increase. Few artists actually owned their spaces and were forced out, unable to pay rent. But it was not only rent that was affected. The success of the art district increased the value of the artworks as well. At this point, local art scenes were no longer thought of as “curious bohemias” but as integral parts of the economy (Molotch, 518).

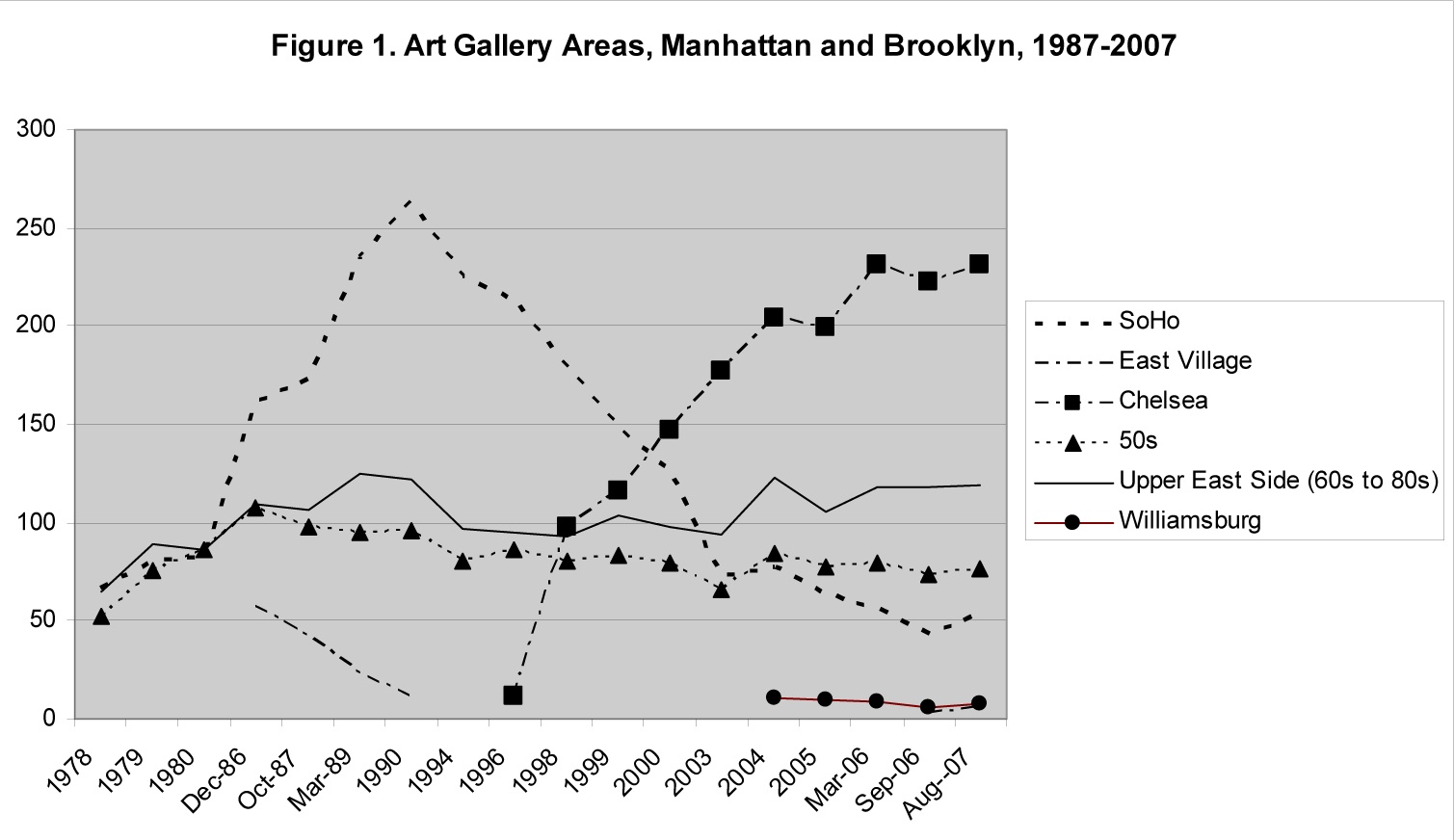

Roughly between 1996 and 2007, artists had reestablished themselves in Chelsea. The number of galleries in the district shot up form about 12 to 260 (Halle, 4). Chelsea began to dominate even the international arts scene. The US consistently represents the highest proportion of galleries in major international art fairs, and of the US percentage, Chelsea galleries represent the majority (Halle, 8-12). One of the characteristics that makes Chelsea so unique is the dominance of small boutique style galleries. These galleries are primarily owned by individuals, not corporations (Halle, 18). Paradoxically, these elite galleries offer more publicly accessible venues for the enjoyment of culture than do public institutions such as museums. The galleries charge no admission fees, and are welcoming to the general public, about 95% of whom do not intend to purchase anything (Halle, 19). In contrast, most museums charge entry fees. These small galleries are able to offer “the very best of contemporary artists available in the most easily accessible form.” This is what distinguishes Chelsea from other “cultural enterprises” (Halle, 20).

Chelsea has developed as an occupational community of artists, distinguishing it from SoHo, primarily a live-work setup. This unique arrangement has given rise to the term “gallerist,” a gallery owner who emphasizes the role of community in the art market (Halle, 21). Chelsea has become one of the best places for emerging young artists to show their work. Acting as test labs, these smaller venues can take more risks than larger museums.

The question now is, will Chelsea go the way of SoHo? Learning from past trials, many of these artists bought their new galley spaces. But most- about 90%- rent their galleries. The leases for most of these spaces will need to be renewed in the next seven to ten years (Saltz, 38). In an article entitled, No Next Chelsea, art critic Jerry Saltz expresses concern for the New York art market's future; “For the first time since the late 1960's, the New York artworld may not have the thing that really makes it different: a one-stop arts district.”

What is likely to happen to Chelsea in the next ten years? Can the small (10%) of gallerists who own their spaces hold down the Chelsea art scene or will it go the way of SoHo? Where might the next art scene emerge (if at all)? Judging from the graph, might Williamsburg develop the next major art scene, or does it lack certain critical elements that were present in SoHo and Chelsea?

(Halle, 6)

Finally, taking into account Saltz's quote, might certain new trends, such as pop-up galleries, be the new locus of the New York art market, or, as Saltz implies, does there need to be a critical density for these galleries, a “one-stop arts district”?

Pop-Up gallery by Chashama in NYC

http://www.chashama.org/locations/current

Bibliography:

Halle, David. Contemporary Art: A 'Global' and loca perspective via New York's Chelsea District.

Molotch, Havey. Changing Art: SoHo, Chelsea, and the Dynamic Geography of Galleries in New York City.

Saltz, Jerry. No Next Chelsea.