DAY 15 Today is Tuesday, January 17th, and we consider the creation of the "art district," and its role in the art market. The readings

focus on the move of New York's contemporary art district from SoHo to Chelsea at the end of the twentieth century. In your response,

discuss either SoHo or Chelsea and the factors that went into making or dismantling each neighborhood as an art district. Many art

world players thought that SoHo, as a contemporary art magnet, would last forever. Today, the feeling about Chelsea is the same,

specially with speculators like the Whitney Museum of American Art, which plans to move from the Upper East Side to Chelsea in a new

uilding by 2015. But many remember the Guggenheim's ill-fated expansion to SoHo. By the time that satellite exhibition space closed,

SoHo galleries had begun their exodus north and westward to Chelsea. You might also site other examples of art districts in other cities

or countries.

Readings

New York City: Soho, Lower East Side

A Gallerist Turned Developer - New York Times.pdf

Read: Fred A. Bernstein, "A Gallerist Turned Developer," the New York Times, March 18, 2007.

New York City: Chelsea and Contemporary Art

Read: David Halle and Elizabeth Tiso, "Contemporary Art: A 'Global and Local Perspective via New York's Chelsea District," in UCLA, On-Line Working Paper Series, California Center for Population Research, 2007

No Next Chelsea

Read: Saltz, Jerry. "No Next Chelsea," in Modern Painters, October 2006.

Art, Bohemia and Economic Development

Read: Elizabeth Currid, "Bohemia as Subculture; "Bohemia" as Industry: Art, Culture and Economic Development," in Journal of Planning Literature, 23, 368-383.{color}

The Highline!

Read: Lisa Chamberlain, "Open Space Overhead," in Planning, March 2006.

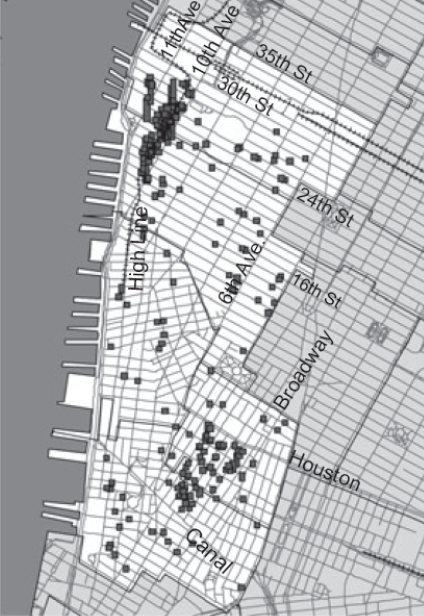

Geography of Galleries in NYC

Recommended Reading: Harvey Molotch and Mark Treskon, "Changing Art: Soho, Chelsea and the Dynamic Geography of Galleries in New York City," inInternational Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 33.2, June 2009, pp 517-531.

Individual Contributions

Chelsea's survival may be in jeopardy. Probably the most important factor in determining its future is the fact that the booming worldwide demand for art is coinciding with a boom in the commercial real estate market. Rising rents proved the downfall of Soho, and many parallels exist today in Chelsea. In Soho, rising real estate prices introduced a flood of fashion boutiques that were much more appealing to landlords than art galleries, and landlords conspired to push galleries out, eventually settling on the then relatively district of Chelsea. As Chelsea grew in stature, the incentive for galleries to relocate there increased, and so began the flood of demand for Chelsea real estate that has made it the artistic hotbed we see today. Since Chelsea could not legally consist of residences, many galleries were insulated from the high prices that could be charged to condominiums, which offered some degree of rent protection; many galleries that could afford it opted to own their own space to further protect themselves from rent volatility. The zoning protection ended in 2005, however, which may help speed Chelsea's downfall as an concentrated art district. The vast majority of galleries in Chelsea do not own their own space; as rising real estate prices coincide with the increase in popularity of Chelsea as an art destination, the increasing demand for limited space may prove prohibiting for many existing galleries, and a severe die-off of galleries could ensue.

A candidate for replacement is the Lower East Side, bolstered by the New Museum of Contemporary Art, which suggests a dramatic and instant rival. The lower density is seen as an advantage by some, as the larger spaces allows for "breathing room," a stark difference from the industrial spaces of Chelsea. Germany also offers a potential rival, as real estate is extraordinarily spread out -- there is no "island constraint" that is present in Manhattan, meaning that location is in greater supply and is not fixed by natural boundaries, which could serve to maintain low prices regardless of any influx in demand. It seems like New York, if it wants to retain its place as the forefront in the international art market, must spread out to survive -- the model of concentration may no longer be viable.

Any gallery wanting to stay in "the scene" needed to make the move along with their colleagues and nemeses to remain a part of the hip and burgeoning NYC art scene which has historically been concentrated in one place - despite the fact that this location is periodically shifting. One might think then that this shift was produced on a whim by a prominent gallery or artist who moved to Chelsea and brought with it a landslide of followers and an epic exodus. The reasoning behind the Soho-Chelsea shift is more complicated than that and has its roots not only in the reputations of the galleries making the move, but also the living situations of the artists creating the work, the influx of culture brought on by an artistic community, the real-estate values as effected by cultural appeal, and the gentrification of Soho.

Soho, though not the first of the concentrated artistic communities in New York, was the most recent. In the 1980s the art bubble exploded. Art auctions sold pieces for unexpected highs, galleries were flourished and many opened, and artists began to move to Soho where they could live and work together in a place with low rent when the upper east side became too expensive. For artists, it is important to stress that while competition and monopoly are assets in other fields, communities and cultural cohesion are important factors for thriving art scenes and work. In Soho, artists often worked where they lived, producing artwork within a community of other living and working artists. Galleries took note of this trend and flocked to this area. Rents were cheap at first, so many galleries and cultural institutions opened their doors. With the artists came the art scene, a cultural mix of hip restaurants, shops, galleries, etc. With the art scene came people to see the galleries, to eat at the restaurants, to shop at the boutiques.

As the area started to develop a reputation as a destination rich in intrigue and culture, its symbolic value as a living environment increased. As its symbolic value increased, the demand and, by economic laws, the rent went up too. Unfortunately rocketing rental prices for work and living places meant that artists who could not afford the increased prices when the rents went up were replaced at the end of their leases by new buyers. The same factors that had drawn so much attention to the area were being replaced by young professionals and commercial shops by the mid-1990s. High end fashion emerged in Soho as a response to the money flowing into the region, and suddenly the artists who had helped to make the place grow could no longer afford to live there. But it wasn't only the artists that moved.

Shopping Map of SoHo in 2005

The galleries began to be forced out too, and in response they moved to Chelsea where the rents were still low and the spaces were larger and more available. In Soho, the rents were growing rapidly. It is assumed that if the galleries were selling lots of art to the rich people moving into SoHo that they would be able to sustain themselves even if the artists moved away. But with the market recession in the 1990s, art was selling for less than it had in years and galleries were struggling to keep doors open. The move by a few prominent galleries was enough to begin a whole exodus. Many galleries moved because they could not sustain rents. Some moved because others were moving and a gallery scene is improved by the presence of many galleries in a concentrated area to draw people like a tourist attraction. Art scenes and gallery presence are not the strange places, the bohemias, of the past but new cultural forms which are desired by cities and populations as proving a certain amount of "economic vitality". Others stayed and tried to weather the storm, only to be overshadowed by the now infamous Chelsea art scene. Many feel that this Chelsea art scene may last forever, but they felt the same about SoHo not long before that. It would seem that memories are short for speculators and dreamers alike.

Chelsea’s rise was partly due to the real estate market1. From 1995-1999 rent prices climbed dramatically in SoHo due to an influx of clothing boutiques. This inflation of prices forced many people and galleries to move to Chelsea where the rent was affordable. With a rise in galleries moving to Chelsea, more people and art events flocked to the developing area. Art Basel is a very well known art fair across the globe. The majority of the galleries showcased in this art fair hail from the United States, with a majority from New York, and specifically the Chelsea region. Its presence in this art fair has helped to create a following and show the work the galleries of Chelsea, exposure that has helped to create a name for this art district.

In Chelsea, there are many galleries, some elite and others non-elite. There are many non-elite galleries in Chelsea, and some gallery owners claim to showcase art that is just “motivated by ‘art for art’s sake’”. This large number of gallery owners helps to explain the “existence of dense concentrations of small galleries” which only adds the to the intricacies of Chelsea as an art district1. Despite the high density of small non-elite galleries, elite galleries still thrive. Elite galleries in Chelsea are typically very easy to maneuver through, and enable the public to see the very best of contemporary artists with ease1. Ironically, many of the lesser, non-elite galleries require much more effort for viewers to look at the artwork because of ascending levels in many galleries (upper-level) 1. Interestingly enough, elite and non-elite galleries both excel in Chelsea, and the region has success on both sectors of the art world.

Chelsea is characterized by numerous galleries and artists and continues to thrive. Artists in the area say that Chelsea galleries for the most part give them more freedom and opportunity than do not-for-profit museums and other institutions in New York or elsewhere. Such liberty in one’s art career is another reason why Chelsea has become a great art district. Emerging artists and established artists alike are drawn to this district marked with changing styles. Chelsea has developed into an “occupational community of people who work in/run/own galleries” and it typically has all the positive attributes of a community.

The region is even characterized by its avant-garde reputation. Some of the success that Chelsea galleries have had stems from the audience who goes to view the artworks present there. If one wanted to be “with contemporary art in a hip social setting, Chelsea becomes the necessary--and reliable--place to go”. If the “it” crowd all gathers in Chelsea, it is no wonder why other individuals in the art world would look to emulate them and visit these Chelsea galleries2. While visiting these galleries they would see art that depicts “major on-going issues in people’s lives” allowing the public to relate to the artwork1. This characteristic of relevance has made Chelsea very successful. People’s tastes and preferences are drawing them to this district. The art resonates with the audience’s lives in an on-going, creative, and interactive way1. Even the city government has become a force that is working to preserve Chelsea as an arts district. In designating the “Special West Chelsea District” the city makes it an explicit goal to “encourage and support the growth of arts-related uses in the area”2.

Looking at the events that have taken place at Chelsea, it becomes clearer which factors led to the development of this great art district. Rising real estate prices in SoHo forced the initial move to Chelsea, where many artists and galleries established themselves. With the increasing population came increasing fame as noted by the large percentage of Chelsea galleries represented in major art fairs like Art Basel. The community enabled emerging artists and older artists to thrive, in addition to elite and non-elite galleries. Significant audiences came to view the artworks. The artwork speaks to the issues in people’s lives and for now the Chelsea art district is characterized as one of the greatest art districts for contemporary art in the world.

Similar factors played a role in the success of one of London’s newer art districts in Fitzrovia. Dealers moved into Fitzrovia after being attracted by its location and trendy image3. The area is very central and there is a lot more space to open a gallery than in the older district in East End London where some galleries were not as accessible. Internationally recognized dealers moved into Fitzrovia making the area more extravagant3. Like Chelsea, people can just drop by to see art in a gallery. This is something that cannot be done in East End.

Berlin has a similar story. Brunnenstrasse is a newer art district, typically for the younger and more avant-garde4. The older district, Auguststrasse, became oversaturated, expensive, and even mainstream. Like the Chelsea art district, Brunnenstrasse has low rents and an artsy vibe that attracts art dealers from everywhere, even New York4. Up-and-coming artists hailing from all over Berlin are also attracted to the region. In addition to all these new dealers, the region is characterized by boutiques, designer bars, and many renovated courtyards that add to the bohemian and fresh feel of the district that Auguststrasse did not have4. It seems as though similar factors influence the change in art districts across the globe.

Picture of Brunnenstrasse in Berlin, Germany:

References:

1Halle, David, & Tisa, Elisabeth. (2007). Contemporary Art: A 'Global' and Local Perspective via New York's Chelsea District. UC Los Angeles: California Center for Population Research.

2Harvey Molotch and Mark Treason, "Changing Art: Soho, Chelsea and the Dynamic Geography of Galleries in New York City," _International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, _Vol. 33.2, June 2009, pp 517-531.

3http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&refer=muse&sid=asfJFKPvrd64

4http://travel.nytimes.com/2007/03/25/travel/25surfacing.1.html\\

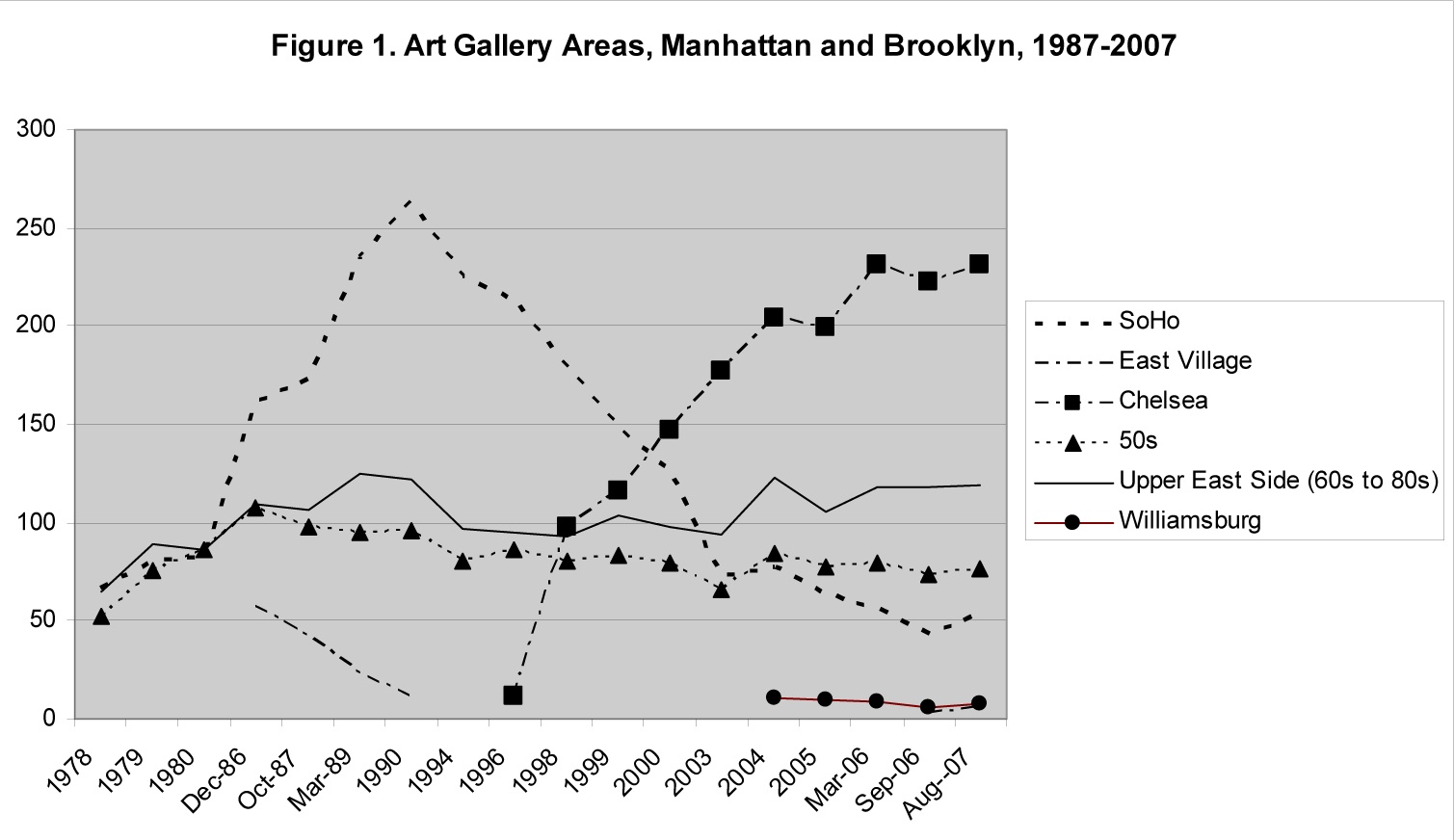

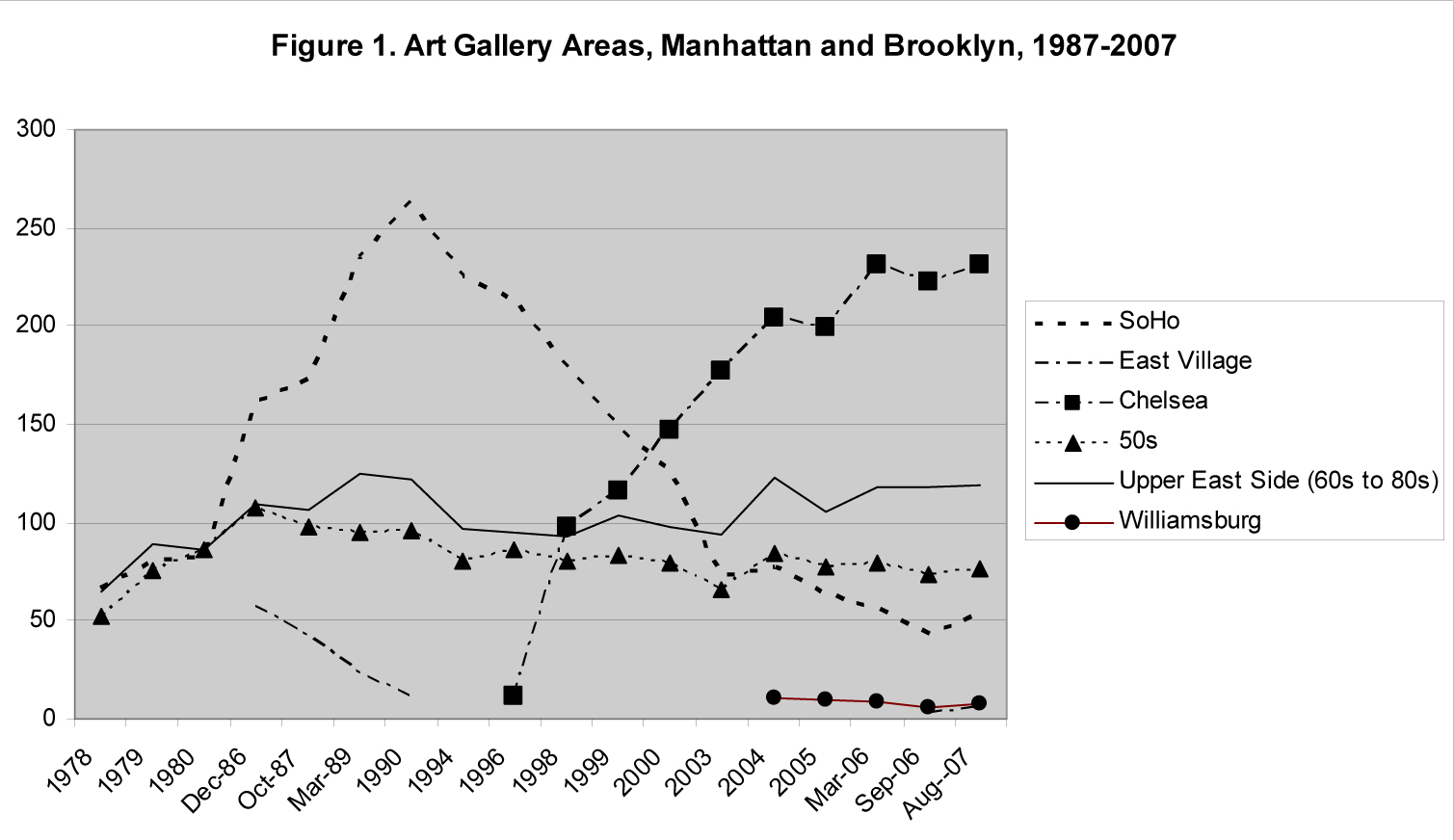

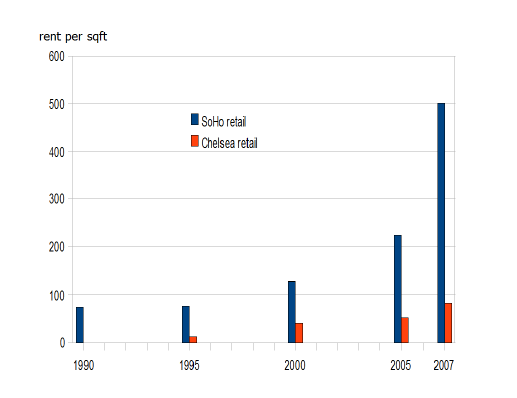

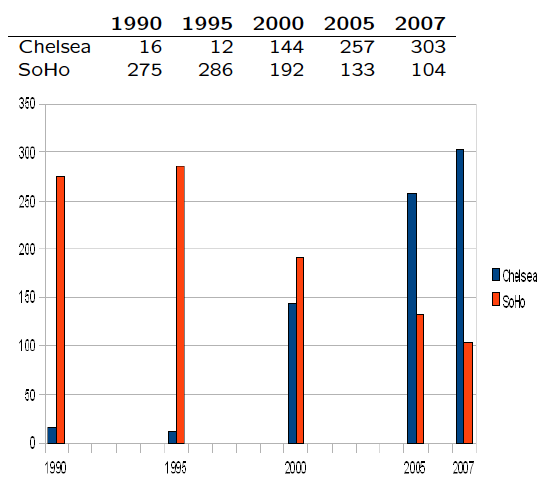

1. Rental rates: Molotoch and Trekson document how Chelsea went from having 16 to 303 galleries, while Soho went from 275 to 104. Their analysis establishes a relatively close correlation between the change in galleries to the change and higher rental rates in Soho, especially for ground-floor rentals. The figures they use in Table 1 on page 524 and the graph in Figure 4 on page 526 show the correlation.

2. The size of artwork: Starting around 1990, “art was getting (literally) bigger” something for which Chelsea was “superior” (Molotoch, 530). Chelsea buildings often had garage door fronts and clear-through floors without columns. As Molotoch and Trekson write, “big space gave rise to big art just as big art demanded big space.” Here is a photo from New York Magazine of a typical store/garage front in Chelsea – many of which have now been turned into galleries. It’s easy to see how this kind of space could accommodate large pieces of contemporary art.

Here is a YouTube video of the David Zwerner gallery which relocated from Soho to Chelsea. You can get a sense of the type of space needed to accommodate a large exhibit.

3. Zoning: New York City designated art galleries in Chelsea as an “as-of-right” use in what was previously a manufacturing-only zone (Molotoch, 532). Chelsea is experiencing what Elizabeth Currid at USC would describe as the “active cultivation of art as a central part of economic development; ” in other words the city wants to economically develop Chelsea with people, “not smokestacks” (Currid, 368).

4. Small Gallery Opportunities: Chelsea has many elite galleries. In fact, Chelsea galleries made up 63% of all New York galleries at Art Basel 2007 ( Halle & Tiso). But interestingly the “vast majority of Chelsea galleries are small shops offering a series of opportunities . . .” (Halle and Tiso). So for the aspiring artist and aspiring gallery, Chelsea provides a lot of opportunity.

Whether Chelsea will retain its dominance over contemporary art galleries remains to be seen. Even though many thought Soho’s dominance for contemporary galleries would last forever, it didn’t. And because so many (90% according to Saltz) of Chelsea galleries rent their space, there is no telling what will happen as more and more leases come up for renewal.

In SoHo, artists lived and worked in the same neighborhood, and the small spaces in the buildings limited the size of the art being created. In the move to Chelsea, where spaces were much larger, the art being produced became much larger but it is hard to determine which led the other first. Most likely a combination of both the changing taste in art towards large-scale work and the availability of larger studio and gallery spaces were equally influential. Interestingly, it appears that most other cities have not typically had this high concentration of art galleries in one art district, but rather a scene that is more interspersed throughout. More recently though, some cities appear to be developing and establishing more solid and defined art districts, especially those in Europe.

Considering the historical movement of the art district in New York, I suspect that Chelsea, like SoHo, will not be the center of the contemporary art scene permanently. The art market has shown itself to be quite mercurial with its tastes, styles, interests, and trends constantly changing. Keeping this in mind, I think it is easy to imagine another move due to any number of factors especially if it is led by one of the innovators or well-known players of contemporary art who could trigger others to follow. As Chelsea becomes more popular and the retailers invade (I was there in November and many high end retail stores had already moved in), the art scene may be pressured to move again. One advantage that Chelsea has in terms of maintaining the area as an art district and preventing the influx of other businesses is the relative lack of transportation to the area compared to that of SoHo. While I think this will certainly slow the business/retail sector’s arrival, it will not prevent it entirely. The appeal of the Highline will also draw commerce and potentially become a factor in pushing the arts out even while its initial purpose was to highlight and strengthen Chelsea and its vibrant art scene. There are already other areas in New York, especially in Brooklyn, that are developing respectable art districts, but whether one of these will be the next SoHo or Chelsea is yet to be seen.

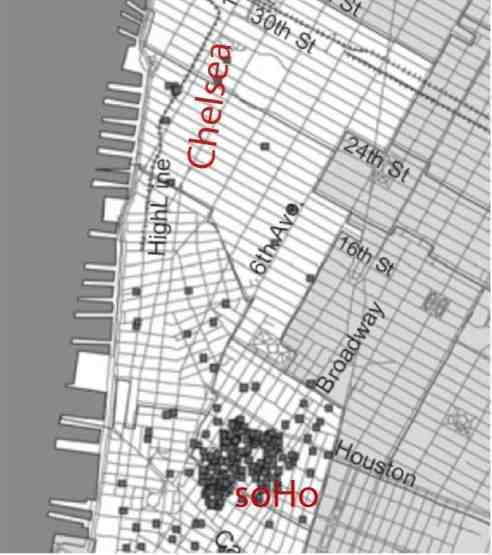

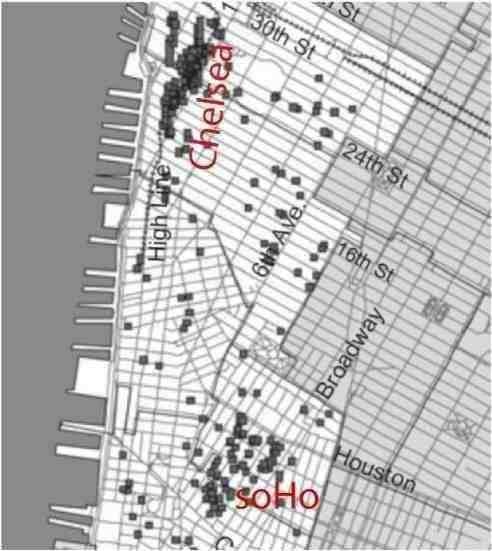

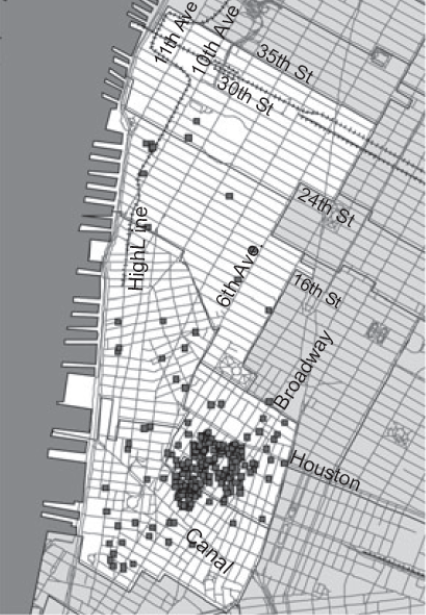

Contrasting images of SoHo (top) and Chelsea (bottom):

Once cannot help but wonder, what caused this drastic shift of the art locus in New York? As many of the readings for today say, the biggest reason seems to have been the rise in rent in the SoHo area. Once SoHo became popular not only for art galleries but for big fashion stores and restaurants, the galleries could not afford to stay in the neighborhood any longer. One gallery moved after another, the majority of them to Chelsea.

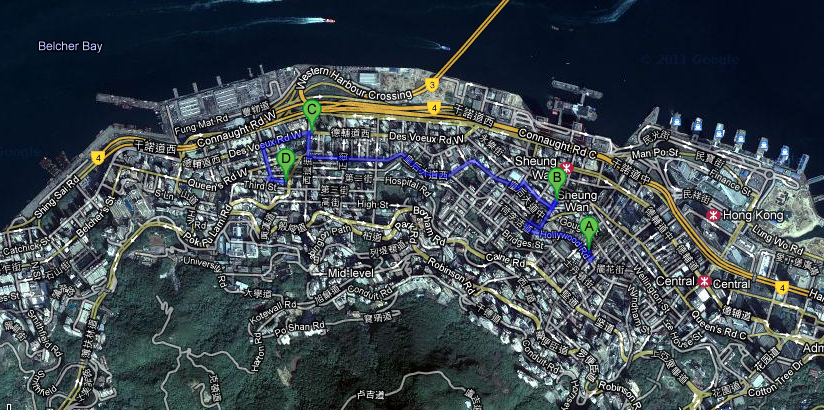

Hong Kong’s art scene seems to be experiencing something quite similar to New York’s. Galleries in Hong Kong started to move out of their So Ho, “South of Hollywood Road,” more than a decade ago when restaurants, bars and galleries moved into it, “pushing out old-fashioned butchers, grocers and soy-sauce makers” (Lau). SoHo got “crowded and expensive,” so some galleries relocated in an adjoining area called NoHo, for “North of Hollywood,” or BoHo, for “Below Hollywood” (Lau). Lau says, “the more adventurous, or perhaps just the more rent-sensitive, are increasingly moving to the old working-class districts of Sheung Wan, Western and Sai Ying Pun,” all of them within a 30-minute walk from the SoHo district (Lau) (see map). Sound familiar?

A gallery in SoHo, Hong Kong

A gallery in NoHo, Hong Kong

http://i.cdn.cnngo.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/inline_image_624x416/2010/07/22/7-madhouse1.jpg

GoogleMap image of Hong Kong (A: SoHo, B: Sheung Wan, C: Western, D: Sai Ying Pun)

.

Going back to New York, New York’s Chelsea started to burgeon mainly because of its comparatively low rent, but to remain as the new center for the contemporary art scene, Chelsea had to have something that makes it unique and attractive. In addition to the big, elite galleries, Chelsea has small galleries owned by individuals. In fact, roughly 60 per cent (210 galleries) of all the galleries in Chelsea are non-elite and have an upper floor location (Halle).

Here are what the Chelsea galleries offer:

Free quality shows for the public - Despite the prolific “bad art” produced in the neighborhood as Jerry Saltz points out, one can also find “good art” among the bad ones, and all for free. Chelsea’s art is about major, on-going issues in people’s lives, so the audience is able to relate and connect to it (Halle).

Freedom and opportunities for artists - Many galleries in Chelsea and the artists whose works they exhibit work on the “art for art’s sake” doctrine (Halle).

A sense of community (“occupational community of gallerists”(Halle))

In addition to these characteristics, Elizabeth Currid suggests that the innate quality of the neighborhood (its industrial chicness) complemented the avant-garde quality of contemporary art (Currid 553). “The art and the neighborhood did not just arise together in the sense of coincident timing but were intrinsic to one another’s existence” (Currid 553). Moreover, although more than 95% of the people who come to the galleries come just to look with no intention of any purchase, these visitors create a kind of social backdrop for the “hip” place to be (Halle, Currid 534). Government-aided projects like the High Line can also make the neighborhood more attractive.

But could the same thing from which SoHo suffered happen to Chelsea in the future? The rent in Chelsea should go up as the area gets more crowded. A small island city, New York’s rental market can get pretty ridiculous. Learning from the SoHo debacle, some galleries with sufficient wherewithal bought their spaces, but the vast majority (90% according to jerry Saltz) signed leases (Halle). What will these galleries do when the rent soars up at the end of their lease? And I wonder, what’s the point in staying in Chelsea if the vast majority migrates to another region, bringing New York’s contemporary art with them?

Currid points out that besides the real estate problem, changes in market value of artifact produced in the area are also important. If the price of the artworks produced in Chelsea go down, Chelsea will not able to survive regardless of how cheap rents are (Currid 535). Should the taste of the consumers change, or they can’t afford to hang big paintings on the walls of their ever-crowding homes, Chelsea will suffer. The galleries will have to either move as a group or dissipate. Jerry Saltz believes that the dissolution of the “one-stop art district” that is Chelsea can be good. Only time will tell.

Works Cited

Currid, Elizabeth. "Bohemia as Subculture; "Bohemia" as Industry: Art, Culture and Economic Development." Journal of Planning Literature. 368-383.

Halle, David, and Elizabeth Tiso. "Contemporary Art: A 'Global and Local Perspective via New York's Chelsea District." UCLA On-Line Working Paper Series. California Center for Population Research: 2007.

Lau, Joyce Hor-chung. “SoHo, NoHo. Sound Familiar?” The New York Times. 29 Oct. 2010. Web. 16 Jan. 2012. <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/30/arts/30iht-sckong.html>.

Saltz, Jerry. "No Next Chelsea." Modern Painters. October 2006.

Chelsea developed as the haven for artists fleeing SoHo after 1995. The reasons for this move are more complex than what is seen at face value. Artists are commonly agents of gentrification, and as the SoHo arts district revitalized, rent began to increase. Few artists actually owned their spaces and were forced out, unable to pay rent. But it was not only rent that was affected. The success of the art district increased the value of the artworks as well. At this point, local art scenes were no longer thought of as “curious bohemias” but as integral parts of the economy (Molotch, 518).

Roughly between 1996 and 2007, artists had reestablished themselves in Chelsea. The number of galleries in the district shot up form about 12 to 260 (Halle, 4). Chelsea began to dominate even the international arts scene. The US consistently represents the highest proportion of galleries in major international art fairs, and of the US percentage, Chelsea galleries represent the majority (Halle, 8-12). One of the characteristics that makes Chelsea so unique is the dominance of small boutique style galleries. These galleries are primarily owned by individuals, not corporations (Halle, 18). Paradoxically, these elite galleries offer more publicly accessible venues for the enjoyment of culture than do public institutions such as museums. The galleries charge no admission fees, and are welcoming to the general public, about 95% of whom do not intend to purchase anything (Halle, 19). In contrast, most museums charge entry fees. These small galleries are able to offer “the very best of contemporary artists available in the most easily accessible form.” This is what distinguishes Chelsea from other “cultural enterprises” (Halle, 20).

Chelsea has developed as an occupational community of artists, distinguishing it from SoHo, primarily a live-work setup. This unique arrangement has given rise to the term “gallerist,” a gallery owner who emphasizes the role of community in the art market (Halle, 21). Chelsea has become one of the best places for emerging young artists to show their work. Acting as test labs, these smaller venues can take more risks than larger museums.

The question now is, will Chelsea go the way of SoHo? Learning from past trials, many of these artists bought their new galley spaces. But most- about 90%- rent their galleries. The leases for most of these spaces will need to be renewed in the next seven to ten years (Saltz, 38). In an article entitled, No Next Chelsea, art critic Jerry Saltz expresses concern for the New York art market's future; “For the first time since the late 1960's, the New York artworld may not have the thing that really makes it different: a one-stop arts district.”

What is likely to happen to Chelsea in the next ten years? Can the small (10%) of gallerists who own their spaces hold down the Chelsea art scene or will it go the way of SoHo? Where might the next art scene emerge (if at all)? Judging from the graph, might Williamsburg develop the next major art scene, or does it lack certain critical elements that were present in SoHo and Chelsea?

(Halle, 6)

Finally, taking into account Saltz's quote, might certain new trends, such as pop-up galleries, be the new locus of the New York art market, or, as Saltz implies, does there need to be a critical density for these galleries, a “one-stop arts district”?

Pop-Up gallery by Chashama in NYC

http://www.chashama.org/locations/current

Bibliography:

Halle, David. Contemporary Art: A 'Global' and loca perspective via New York's Chelsea District.

Molotch, Havey. Changing Art: SoHo, Chelsea, and the Dynamic Geography of Galleries in New York City.

Saltz, Jerry. No Next Chelsea.

In many cities, not only New York, art galleries tend to be centrally located in one region all clustered together. On first thought, this does not seem like a good idea because it is putting competition right next door, however the art world works differently than that of the corporate, chainstore type world. While it would be unreasonable for all of the cities fast food restaurants to concentrate themselves in one location, this clustering works for the Art world. The reason it works is because it becomes a center, a community of artists and their dealers. When art galleries first began opening in SoHo, it was because the artist population already lived there, and it was more profitable to move to where the center of the art universe resided, hence the influx of galleries moving into SoHo. However, with this rise in activity, the previously lax nature of SoHo, with their lowered rent, became more populated and thus the rent increased with the crowds, causing more artists to once again move to a cheaper neighborhood where they could continue their work. Once museums such as the Guggenheim expanded into SoHo, the area was no longer just an artist community, but also brought in crows of people and tourists coming to catch a glimpse of the next big art star.

Guggenheim in SoHo

For this reason, the art center in Manhattan moved to Chelsea, which was similar to SoHo before the influx of galleries and people. This however, was not a small, long-term move,but rather a sudden change that seemingly happened overnight. Soon after the artists moved to lower rent apartments and work spaces in Chelsea, the galleries followed them,demonstrating the same trend that changed SoHo into the art center of NYC in the 1980s. However, now it seems as though the trend that forced galleries to move from SoHo to Chelsea might be taking place again. By moving a the Whitney Museum of American Art from the Upper East Side to Chelsea, the same outcome will probably happen again. The rent and foot traffic will increase in Chelsea to the point where the artists and galleries move yet again to another part of Manhattan, such as the Lower East Side, or possibly out to even cheaper areas off of the island.

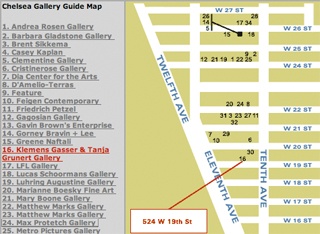

On this website one can see the sheer amount of galleries in Chelsea, as opposed to other locations. SoHo doesn’t even have it’s own category on the website, whereas Chelsea does, and then is further divided by galleries on each specific street.

http://art-collecting.com/galleries_ny.htm

This article discusses Chelsea’s art scene, and how it continues to grow:

http://themidtowngazette.com/2011/10/chelsea-galleries-remain-strong-despite-development/

Gallery in Chelsea

Gallery in SoHo

Chelsea was an early center for the motion picture industry before World War I. Some of Mary Pickford's first pictures were made on the top floors of an armory building on West 26th St. there was also the Elliot Chelsea house that contained an off-Broadway theater and fine arts programs. As New York's visual arts community moved from Soho to West Chelsea in the 1990s, the area has become one of the global centers of modern contemporary art. The West Chelsea Arts District is home to over 370 art galleries and innumerable artist studios. The area has also become home to the modern dance companies and well regarded performance venues and theaters. Since the mid-1990s, Chelsea has become a center of the New York art world, as art galleries moved there from Soho. there are more than 350 art galleries that are home to modern art from upcoming artists and respected artists as well.

Soho,After the city abandoned LoMEx, was still left with a large number of historic buildings that were unattractive for the kinds of manufacturing and commerce that survived in the city in the 1970s. Many of these buildings, especially the upper stories which became known as lofts, attracted artists who valued the spaces for their large areas, large windows admitting natural light and dirt-cheap rents. Most of these spaces were also used illegally as living space, being neither zoned nor equipped for residential use, but this was ignored for a long period because the occupants were using space that would probably have been dormant or abandoned in the poor economic conditions of the era. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Soho neighborhood had changed once again, earning a reputation as a manufacturing and commercial zone during the industrial revolution. The New York City’s population was exploding from immigration, and Soho was no longer a suburb of downtown Manhattan. Retail stores had gone further north. Large loft apartments gave artists the space they sought for their work, and served as a creative forum for carving out residential housing in what were once factories and commercial lofts.

Galleries in SoHo and Chelsea in 1995

From the history of these two places, my conclusion is that, the primary reason for this entire shift is monetary issues in relation to price of buildings. Soho, was once the driving city of art galleries because the buildings were huge, and cheap, and it was the delight for all artist, gallery owners and museums. When soho started to become a more industrialized and commercialized district, naturally the cost of living became high, and for galleries and artist who I believe were not making much then, they had to move and what better place to move to than Chelsea, a place which also had a historic artistic culture. I believe that the move was not only because it was an artistic center, but it was also cheap, and there was space to occupy all these galleries that moved there. Now the fact that there was an immense migration does not mean that soho is no more artistically inclined. There are still galleries all over the place in soho.

Galleries in soHo and Chelsea in 2007

To think that Chelsea will eventually end up like soho, is impossible. I say this because of many reasons. First, space is very important, and NY city lacks space in a neighborhood to have a new move of migration. Secondly, galleries and artist, at least for the ones that are represented in galleries and museums have money. The art world is making enough money to be able to pay for rent should they get any higher, because the hunger for acquiring art is high, money has become the main goal for these people and they are making it. Also in this current globalized world, there is no doubt that, other companies will move in quickly to a newly emerging community which makes money, that will turn it into an industrial and commercial neighborhood in a few years.

I think that Chelsea has grown to have a strong foundation and established stronghold as the art center of the contemporary world and it has come to stay. There might be extensions of this, but the headquarters will be Chelsea.

The areas Chelsea and Soho in New York City are most famous for the sale of contemporary art. They have the largest number of galleries of any city in the world. Chelsea and Soho are considered “transient gallery locations” while Midtown is a “stable gallery location” therefore Midtown has not been included in my response as it appeals to a different audience and excludes contemporary art.

After 1995 Chelsea developed as the central area for artists forced to leave SoHo because of rent prices. As SoHo gentrified, rent increased, there was large in flux of wealthy people who could pay the increasingly expensive rents, thus kicking the struggling artists out. The “affordability squeeze" was a cause for galleries to move to Chelsea. Gentrification does not only depend on rents but also on prices of the products being sold. As the Molotoch and Trekson document illustrates, rent was not the sole reason for the move to Chelsea. As the local art scene in SoHo began to fade and the area was not longer a “curious bohemia” (518). As the artists moved, many gallery owners decided to move as well.

Cost of Rent per sq ft in Chelsea and Soho over a 17 year period. SoHo rent increased a huge amount as the area became gentrified and a tourist hot spot.

- When considering a location for a gallery important things to consider are:

- An Attractive location: to which kind of audience?

- Affordable location: how much is it worth to pay?

- How large should the space be?

- Suitable location: does it fit to the art to be sold?

- Distance to competitors/collaborators?

Chelsea was more affordable for artists & gallerists, it allowed galleries to have larger spaces and the new location fit with the new up and coming contemporary art movement. In Chelsea there are many boutique style galleries which also cater to a different kind of audience. The boutique galleries in Chelsea act as museums without entrance fees, therefore they are accessible to a much larger audience. Even the audience that comes into the gallery knowing they won’t by anything is affective promotion for the smaller galleries as there is a word of mouth factor. Many galleries located in Chelsea are more, quaint and small compared to Opera Gallery, still located in SoHo, which caters to a very "show boat" kind of buyer who enjoys name brand art and is likely investing in art for the social aspect and the price tags bragging rights.

The number of galleries in Chelsea and SoHo over a 17 year period.

In terms of the future of galleries in Manhattan i believe overtime galleries will migrate from Chelsea just as they did SoHo. Galleries like to follow the artists, however; galleries change the economic value of the district. Galleries tend to cause gentrification by turning cultural into economic capital. Galleries spur social and economic revitalization. Often artists cannot keep up with the environment the galleries create, thus artists move and galleries once again eventually follow. This trend is already evident in the establishment of galleries in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Williamsburg is known as the newest artist hang out. I believe galleries will see the environment artists are creating in Williamsburg and want to capitalize on the movement. As the Molotoch and Trekson document illustrates the local art scene is important for galleries to thrive. Chelsea has become gentrified and is no longer an area where struggling artists can live, i believe the SoHo- Chelsea cycle will continue.

The rise of Chelsea came with a phase out of the SoHO art gallery scene. A Guggenheim exhibit featured in SoHO closed just as the last remaining galleries were moving. The main reasons for the switches from SoHO to Chelsea can be derived from the rising rental prices in SoHO and the change of zoning laws in Chelsea. The fact that SoHO was a previous art destination was a double sword. In one respect, it created a center for culture and art, in another it drew people and businesses to the area so rents were forced up. The zoning laws in Chelsea were also changed from the area being zoned for industrial purposes, to galleries falling into the “as of right” compliance.

The low rents of Chelsea drew galleries to the area. The interesting aspect of these locations is that both SoHO and Chelsea are not near the ultra elite of the upper east and upper west side. Instead Chelsea hugs the west-side highway in a previously industrial area of town. SoHO currently is filled with high-end fashion stores. Over run with boutiques and walk up apartments, the rents are currently sky-high and nearly impossible for a gallery to afford.

The Highline perfectly parallels the art expansion towards Chelsea. The highline is a elevated train track which runs along side the west-side highway. It has since been abandoned for use for over 30 years and was just an eye sore for the people of the area. In 1999 the highline was taken over by the city and turned into a trail for the public through the Rails to Trails Act. It has turned an industrial eyesore into a place for the public and a cultural attraction. Many New Yorkers believe that Chelsea with such concentrated art galleries exhibits a similar place for public and cultural attraction.

One of the specific draws to the area is its reputation as the art gallery center of both Manhattan and the world. With over 300 galleries in the Chelsea area it is no wonder why the overwhelming majority of famous art shows (such as Art Basel) feature Chelsea galleries. Even in international shows the amount of galleries from Chelsea trumps the number from any other country let alone city (or part of a city).

Part of Chelsea which makes the location both a cultural icon and an economic powerhouse is the fact that there are both elite and non-elite art galleries. While some of the art galleries are focused on bringing collectors to the art market, many are legitimately out there for the sole reason of connecting the consumer with art. The proximity of all these galleries so close together increases competition, but provides an unparalleled art scene. The lower east side which has only a handful of galleries is known for bringing great art and many in the art world visit monthly. However the proximity of so many galleries in Chelsea means that artists can be seemingly noticed while not being at the most elite galleries. Further, the opening of one new gallery does not affect the others, regardless of how good or how bad the art being shown is.

The East End in London has similar features to Chelsea. In the 1800’s the East End was a heavily industrial area. Because of its proximity to the water, the East End was home to many ship building companies and was a prominent port for the city of London. Currently the area houses some of the best galleries in the world. Despite being known as one of the poorest areas in London, property prices are at all time highs. Similar to SoHO and Chelsea, there are questions as to where the next art scene will be located because of rising rents within the East End. Many have speculated that the galleries may move east to Sundry.

Consider & comment:

Please use this space to respond to your classmates' work and to engage in lively discussions on the day's topic. Keep your comments concise and conversational by responding to others, rebutting or supporting their ideas. Use the comment box below for these observations.

8 Comments

user-5b6bf

It is pretty interesting that the art world has generally clustered around several distinct centers such as Soho or Chelsea. It makes sense, given that most of the drivers of the art market are prestige and perception-based, and that having high brand recognition for a particular neighborhood or district probably increases the value and status of the art and galleries that can claim the district as their primary location. However, the largest costs in the art market are sunk, such as location, storage and overhead, and it would make sense for a gallery to minimize these as much as possible, as they have the biggest effect on their bottom line. Galleries do not want to be associated with commercialization, or described as profit-maximizers, as this connotation is seen as diminishing the value of art, which is important to collectors and artists, so they are likely to overlook the huge cost increases of a primary location in an area with exorbitant real estate prices like Chelsea, as the increase in costs might be offset by the increase in demand or prices that follow from location in a prestigious district. Do you see this trend continuing? Do you think the art market might eventually become cost-conscious enough to accept non-concentrated locales in an effort to realize lower cost outlays? Or will every gallery always follow current location trends in an effort to capture public demand that largely follows these transitions? Soho and Chelsea seem to both be experiencing popularity that only lasts about twenty years, so I feel like relocating costs might become very substantial if rising real estate prices continue to force relocation so often.

user-c6d08

I think I could see this trend continuing. It seems to be that the operations of many industries, including the art industry, are governed by money. It seems that the location which will allow artists, dealers, and galleries to make the most money will prevail. I think as long as the the world renowned artists are concentrated in locale, it won't really matter where it is, because eventually people will flock there and it will soon be known as another popular art district. Such is the case it seems in newly emerging art districts. I really think money governs everything sadly

user-9c486

Charles, I don't think the locale for contemporary art galleries will change from a cluster to non-concentrated locales. I think the galleries want to be near each other, as that provides more of an incentive for people to come to the area; it becomes the known location - which in turn brings in bigger crowds. It allows for an easier exchange of ideas amongst galleries throughout the area.

Also, it becomes easier to secure favorable zoning regulations when so many businesses of the same type are in one area, for example, New York City zoning art galleries in Chelsea as an "as-of-right" use. I think that being part of a cluster, such as the galleries in Chelsea, is a win-win for all involved.

user-11970

Yea I agree with you daniel, actually the main reason why the galleries started to move to chelsea was because the artists were moving there, and as the galleries cannot operate without artist, they moved there also. I think it just serves them better if there are together, not only do they learn from each other, but they help form a strong foundation to keep the market stable, and also make it easier to transport works from one gallery to the other

user-fd7c0

I think it's possible that the contemporary art scene in New York could expand to various locations rather than just one main location as evidenced by the growing art districts in other areas such as Brooklyn (DUMBO - Down under Manhattan Bridge overpass, and Williamsburg), although it tends to like to stick together and there are some definite advantages to that. Overall I think it's really hard to predict what will happen next with the art district given the ever changing nature of art and the art market.

user-e58b5

I have been struggling with these issues of location as well as I continue to do research for my final. I am writing about the architecture of the exhibition and the development of exhibition spaces in relation to the art market.

It does seem, as the Molotch article mentions, that "face to face contacts are especially important... proximity helps establish relationships between buyers and sellers" (Molotch, 518). I think that to a certain extent this experience is irreplaceable. But I am noticing a trend in my research, where the market demand for new exhibitions ('the age of the art fair' 'the age of the curator') places less emphasis on physical location and more on event, including traveling exhibitions, fairs, biennales, pop-ups... It seems that social media platforms (facebook, twitter...) in conjunction with word of mouth, are able to generate enough attention for these events that cannot rely on an established physical location.

Two really interesting pop-up organizations that I came across:

Chashama- a NYC organization that links artists with vacant storefronts to create temporary exhibitions: http://www.chashama.org/

Openhouse- a Manhattan gallery space which can be rented out for any type of exhibition/event from indoor park to art exhibition to impromptu dance club: http://www.openhousegallery.org/category/travel-pop-up

Perhaps there will always be an arts district, as the experience of face to face contact is irreplaceable. But I don't think that this rules out decentralized exhibition spaces, which may equal or even surpass arts districts in terms of market share.

Cheryl Finley

Thanks all for your enthusiasm for this topic. Yes, Charles, the coincident rise of the art market and the real estate market may cause some problems for Chelsea gallerists, but I doubt it, at least not yet. This was the case in Soho, but the influx of retail clothing stores and boutiques that were willing to pay higher rents (and the concurrently cheaper, larger spaces able to accommodate contemporary art in Chelsea) was the driving factor of the Soho art district's demise and the Chelsea art district's rise. The German case in Berlin is an interesting one and I agree it's one of the most happening places in the art world today -- cheap, good food, large spaces, easy access, multiple price points, etc. June, thanks for offering up the fascinating example of Hong Kong Noho/Soho art districts. Charles, your question that about concentrated gallery districts is a good one and I agree with many of the responses your classmates have posted. As Daniel states, its a win/win situation when the galleries are clustered together. And as Dalanda and Elena suggest, these districts exist in a number of different places. While Chelsea may experience some decline (although I doubt it, as the Whitney is building a new contemporary space there and the Highline as Nicholas pointed out is one of the major draws for tourists, health enthusiasts and contemporary artists and musicians as well), there are other up and coming and established art districts in New York City, including the Upper East Side around 76-79th and Madison (near the Met); 57th Street (near the Fuller Building); the East Village (still has galleries); and in Brooklyn near Dumbo and in Clinton Hill.

user-75024

Between day 15 and 16 I am left wondering what city and country government's role should be in creating a viable place for art. On one end of the spectrum, you have the Guggenheim effect, which essentially pushes the government to promote tourism and art appreciation. yet, on the other end you have a hands off mentality, letting galleries move where rent is cheapest and letting worse galleries go bankrupt. I think both have their pluses and minuses, however it is interesting that the Guggenheim effect seems to be limited to large museums and not a large number of smaller galleries. I would be interested in seeing an example of a place which has actively promoted galleries like the ones within SoHO and Chelsea.