"Christie's Auction Room", by Thomas Rowlandson & Augustus Charles Pugin from The Microcosm of London, Volume 1 (London: R. Ackerman, 1810).

Located on the south side of Pall Mall, Christie's has been auctioning high end commodities, ancient artifacts, art, jewelry, furniture, and other personal properties since 1762. The sales rooms are large, light, and airy, simply furnished, and tastefully appointed. Pre-auction viewings are conducted and bidding by proxy is allowed. Owned and managed by John Christie.

Going once: A packed Christies sale room looks on as telephone bidders vie for the most important (and the largest) of Monet's Waterlilies, sold at Christie's, London for an astonishing £40.1 million on June 24, 2008, setting a record price for the artist and a record for any Impressionist painting.

DAY 10 Today is Thursday, January 12th, and we are examining the role of the auctions in the art market. In 2012, Christie's will be 250 years old.

How have the bidding room, the buyers, the sellers and the works offered for sale changed in the last 250 years? Just a quick examination of

the two opening images on this page should provide some clues. Read Sarah Thornton's chapter on "the Auction." Choose a recent sale of fine

art at a noted American or European auction house (or their subsidiaries in Asia or the Middle East) – and discuss its significance with regards

to some of the points that Thornton raises about auctions and the players involved.

Readings

Read the following excerpt on "the Auction" from Seven Days in the Art World by Sarah Thornton (New York: W.W. Norton, 2008).

Watch Christie's' Christopher Burge in action selling an Andy Warhol large Campbell's Soup Can, silkscreen, 1962 for $23.8M (including buyer's premium):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boaFiyICN0w&feature=related

Further Reading "Show me the Monet... Impressionist's water lilies go for record £40m"

Individual Contributions

Auctions provide a key location and market crossroads for these observations to take place. The reading concerned itself with Christies, arguably the premier auction house in the world, especially in its New York location.The entire process, from the "specialists" to the methodology of the sale to the auctioneerChristopher Burge, is designed to achieve the maximum bid possible as a result of the proceedings. The auction house take a percentage as commission, perfectly aligning the auction house's interests with value maximization, which, on paper, should be equivalent to the interests of the artist or vendor. This mindset represents the majority of the auction market, as Sotheby's and Christies together represent an astounding 98% of the auction market. The auction houses have often built personal relationships with many of the key buyers, knowing in advance which are likely to bid and able to provide reliable estimations of final price. The auction house is set up to produce a "high society spectator sport," with the actual bid representing as much of a status symbol as the ownership of the art itself. There is a much-described "rush" or burst of adrenaline when a bid is made in front of all the prestigious watchers and an even greater artificial high when the painting is "won." Winners of art will be published in art magazines and other publications for regular circulation, as the mere ability to buy an expensive work of art generally carries greater value than its ownership or display. Huge names can suddenly produce intense fluctuations in art; for example, the "Larry Gagosian Effect" occurs when rumor states that Gagosian is about colllect another artist in his gallery, and everyone immediately attempts to purchase art, in anticipation of skyrocketing prices -- Gagosian often "protects" his buyers at auction with large bids. Many artists protest this impersonal portrayal of art, rejecting the "asset" vocabulary of the new commodity, often not attending the very auction in order to maintain their "purity." Others, such as Hirst, welcome the superficial demand created for the art and the higher economic value it carries, and have profited from it due to market savvy and ability. Dealers, seeking to promote their artists, often won't sell to collectors known for "flipping" art in auction settings, as they generally view the auctions as immoral or evil. Furthermore, auction prices can wreak havoc for an artist's career: a singular high price can set unrealistic expectations for the artist's future, and failure to meet these prices in the future could result in swift loss of demand for the artist's later work. On the other hand, high prices can catapult an artist into the public eye, but failure to sell and having the artwork "bought-in" by the auction house can produce humiliation to a career-ruining degree. Other players, such as art consultants who gain commission for he purchase of paintings for wealthy collectors, serve to exacerbate the situation, as their job revolves around inflating the prices of artwork to the maximum extent through salesmanship, flattery, or exaggeration. Auctions ultimately provide the illusion of liquidity, which in turn produces confidence, creating an increasingly subjective and artificial market -- many artists doing well now will have zero value in ten year, as auctions have short memories.

This is the first time since the 1950s that art has been shown to this much fanfare. Prior, artists like Picasso made their careers in the private sphere, seeking to find patrons themselves who would support and commission art, and deliver the artist to prominence. Now, the high spectator-aspect of art, as well as the abnormally high returns and ongoing bull market which has propelled it it into a relatively attractive investment opportunity, art has converted into more of a commodity that a product with unique intrinsic value. Time lags between the studio and the resale market are decreasing, as secondary markets are gaining prominence and collectors are increasingly seeking to purchase art for the return on value rather than its ownership and appreciation. In fact, there is a shortage of supply, as consumer run out of early or ancient works and consequently are constantly seeking newer, younger art. It is a buyer's market, but a commodity market with its individual piece losing unique value.

An example of a gigantic Christie's sale is the 2008 sale of Monet's Le Pont Du Chemin de fer a Argentuil for $41.8 million. The auctioneer waits over 90 seconds before accepting the final bid, almost twice as long as the entire previous auction, in an attempt to expertly eke out the absolute highest bid possible. It is a very tense minute and a half, as everyone seems to be looking at everyone, sharing disbelief at the price and excited at the prospect of such a large sale--you could almost hear a pin drop. The buyer ultimately remained anonymous, but whether he elected to eventually reveal himself is unclear. The high price could perhaps be explained by the fact that this was a very old painting, by normal contemporary auction standards, and the fact that there is very little current supply of traditional paintings means that they can command a high premium when lured out of collector's mansions. A picture of the painting is below, as well as the video of its sale.

Watch the sale:

Cady Noland - Oozewald, 1989

The Image is Oozewald, an installation sculpture by Cady Noland created in 1989. Cady is considered to be an influential member of the art world in the late 1980s and early 1990s. She then promptly removed herself from the art market. This move has made her work scarce and has left a place for her work to grow in value as the demand can potentially exceed the supply which has ceased to increase. An article on the political significance on her work highlights the importance of her American political commentary and the minimalistic movement.

In November of this past year, her above sculpture sold for more than double the high estimate of the action at Sotheby's in New York. The estimated low of $2, high $3, and selling price with buyer's premium of just over $6.5 million. This is a prime example of the premium prices being demanded in the auction house market by established collectors, dealers, and advisors. The market is in a bubble. Prices are soaring for contemporary works, and these works are being traded by powerful players for extreme monetary gain.

There are some collectors who do not resell the work they buy, but prefer to hold onto it as selling can be taboo. However, this behavior is mostly indicative of the primary market where works by young new artists are sold for the first time. In the auction houses, with the rare exception of incidences like Hirst's selling of the Pharmacy works, the pieces going up for sale are on the secondary market and are thus thought of more as an investment opportunity than a sentimental buy for people looking to enrich their art portfolios.

Sotheby's Auction House

Until recently the art of living artists was sold privately, with only work by masters on the public radar. The prices of the privately sold pieces were thus not necessarily common knowledge. With the recent trend in the auction houses of selling contemporary art, though usually no fresher than 2 years old, an artist can be branded by the auction house and this branding will inevitably raise the price of their work. People publicly see the new artist among their respected and established peers and ultimately associate that young artist to be of the same caliber (and price range). Yet when an artist like Cady Noland stops producing art work, it is like she has died and the supply of new work by her has been cut off from the market. Therefore when her work comes to the lot, there is the palpable tension created by scarcity and the "need to buy the work now".

Where the market used to thrive on the work of the great masters, a scarcity effect has limited their sales as well. Since the masters are long gone, and museums or other institutions are starting to collect their pieces, it is rarer and rarer to see them offered up at auction, as many people are unwilling to let them go. When they do happen to be released, unprecedented bidding wars have broken out causing record high prices and a sense of urgency on the part of the buying party. This being true, the market is moving towards offering more and more young artists because they are "running out" of work to put up, and being forced into a more contemporary market within the houses. Also, because the masters are being held and the contemporary works are being traded, many financially savvy collectors are seeing the art market as a mode for investment with quick, steep returns when their taste is right (or their advisors are good). Art investing is a more recently pervading fad. Before where the only acceptable reasons to sell in the art world were the 3 Ds, a 4th D for dealers has been added where many are selling for money.

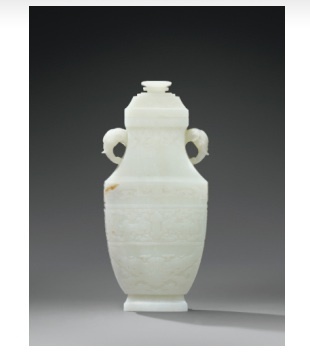

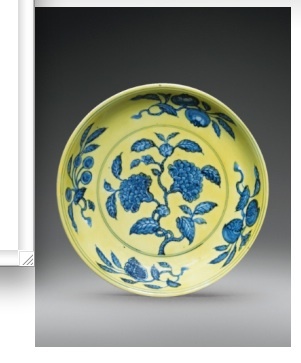

A large blue and white archaistic vase of the Ming dynasty, Wanli mark and period (1573-1620) had a Lot 67 estimated price of 200,000-300,000 EUR. Also in this collection was a blue and white dragon basin from the same reign with an Lot 68 estimated price of 150,000-200,000 EUR and a Ming Dynasty, Zhengde mark and period (1506-1521) yellow ground and underglazed dish with a Lot 75 estimated price of 150,000-200,000 EUR.

In the excerpt from Sarah Thornton’s book, Seven Days in the Art World, she discusses the experience at an auction which revealed several intricacies to the whole process. One major characteristic of auction is that it is a place where “the art world [gets] its financial value. [Auctions] give the illusion of liquidity”. This is very evident by the fact that works of art at auctions are reduced to pieces of monetary value. This is also present by the sale of the pieces from the Art’s D’Asie collection. These works, dating back to the Ming and Qing dynasty, are reduced to their monetary value rather than being appreciated as valuable, historical, art. During the Ming Dynasty, culture developed rapidly and the economy sold many commodities including porcelain. Before the 16th century, the Ming dynasty was even a leading country in scientific development. Then, by the middle of the 18th century the economy of the Qing dynasty had reached its peak and spanned three emperors including Emperor Qianlong. This age was called “the golden age”. Works from both these dynasties has great value and have historical implications greater than just monetary value.

It is likely that they were obtained quickly, within minutes like at a typical auction. In the excerpt, Thornton notes that items that are successfully sold are done so in minutes. Deals are made quickly, and serious collectors usually do the purchasing. In the words of Amy Cappellazzo, Christie’s international co-head of postwar and contemporary art, “art is more like real estate than stocks”, implying that there are different degrees of wealth that can be obtained and displayed through the purchase of art. One can gain riches and display his or her wealth with a condo, or with a penthouse. Stocks are always stocks, simply with different values. Buying the items in the Arts D’Asie collection may reflect this notion. The collection may provide a serious collector with a quick, non-time consuming means of collecting art from a powerful time in history, without having to deal with primary dealers and the red tape associated with interacting with them. With this art, they can work towards increasing their status in the art world and monetary value. After all, auction is a “high-society spectator sport” where people go to be seen and meet and greet “the money”.

Some of the works in the Art's D'Asie collection:

On the left is a porcelain vase from the Qing Dynasty

On the right is a porcelain plate from the Ming Dynasty

References:

Thornton, Sarah. Seven Days in the Art World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2008. Print.

http://www.travelchinaguide.com/intro/history/ming.htm

http://www.travelchinaguide.com/intro/history/qing.htm

http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/2011/arts-dasie/overview.html

The auction house of today has it’s own kind of branding and marketing. What I mean by that is it seems the auction is as much about the star power of the auction house, its auctioneer, and its clientele, as it is about the work being auctioned. It looks so easy to get caught up in the moment and spend more than you ever wanted to – which I believe is a product of successful marketing by the two major auction houses.

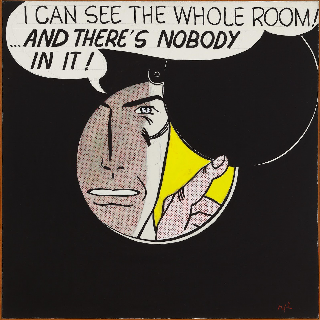

An example of a recent and notable sale is Roy Lichtenstein’s I Can See The Whole Room…And There’s Nobody In It! It sold for $43.2 million at Christie’s in November, 2011.

Here is a video of the piece being auctioned off at Christie’s:

After watching this video of the piece getting auctioned off, I realized how well the reading describes the typical auction. The Lichtenstein piece was auctioned off at Christie’s by Christopher Burge. His charming personality as described by Thornton is seen in the video. While he does seem to have “tight control over the room” (Thornton 5), he has a way of engaging the crowd that keeps everyone involved, whether or not they are bidding. I think any major auction ar Christy’s or Sotheby’s is really well described by Thornton who calls it a “high-society spectator sport” (Thornton 9).

Burge does a good job at spreading the energy throughout the bidding room. "People who buy at the auction say that there is nothing like it: your heart beats faster, the adrenaline surges through you” (Thornton 10). In the reading, Thornton explains that before the auction, Burge studies the background of the potential bidders. Although Thornton mentions that Burge has a script to read from, it doesn’t seem like he is doing so. The auction “crowd is international” (Thornton 12), which explains the display shown in the Lichtenstein sale video that has many different currencies. Burge, with his British accent, makes a good auctioneer as it brings a sense of Europe to the American auction.

Does anyone else think the excitement generated by a high profile auction in and of itself causes people to bid higher?

Here is a link to a website in which Sarah Thornton comments on the Lichtenstein sale: http://blogs.reuters.com/felix-salmon/2011/11/21/why-you-cant-always-trust-auction-results/

Here is a link to a Wall Street Journal article about the sale: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204190704577026963186239408.html

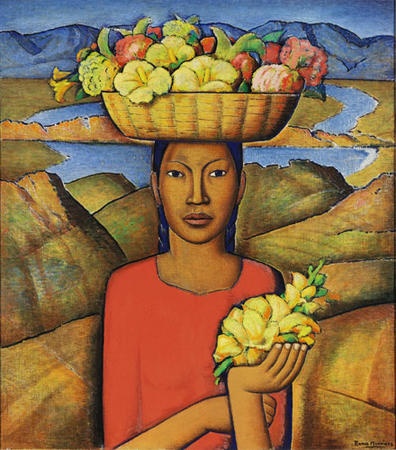

I suspect that similar to the contemporary art auctions that Thornton described, the Latin American art patrons are an insular group in which, “With few exceptions, everyone sits in exactly the same spot they did last year.” While much of the Latin American art for sale is very significant and fine quality art, the market is not nearly as strong as that for contemporary art, for which a sale on November 9, 2011 brought in $315,837,000. The “specialists” involved in the Latin American art auction were Carman Melian, Ana Maria Celis, and Andrea Zorilla. Melian had an important role in the 2006 sale of Frida Kahlo’s “Roots” which was a record sale for Kahlo’s work at $5.6 million. As mentioned by Thornton, the catalogue is the main marketing tool for the auction. For each piece, the catalogue for this auction included a color picture, provenance and exhibitions, a list of literature regarding the artist, and a “note” that provided a brief biography of the artist and description of the work.

By comparing the images of auctions by Christie’s in 1810 and 2008, and Thornton’s reading about auctions, it becomes clear that the auction world has changed in some ways. The auction room appears to be much more organized (assigned seats) and crowded, with less room for movement in its current state than in the past. Much of the art displayed on the walls has been replaced by television monitors and a “scoreboard or currency converter.” While many buyers and sellers surely have similar motives to those of the past, I think there is presently a stronger emphasis on art as investment. In addition, buyers can now participate in an auction without being present through the use of phones and the internet which obviously was not possible in 1810. The type of work sold at auctions has also changed. Before the 1950’s, art by living artists was not commonly sold in auctions because, “living artists are perceived as unpredictable and inconvenient.” This has changed drastically as much of the art now sold is by living artists and the demand continues to rise.

Here is a link to a Youtube video of the most recent auctions of Latin American Art by Sotheby's and Christie's in New York: http://youtu.be/NxQW2RiuIwM

Here are Tamayo’s “Watermelon Slices”, Botero’s “Ballerina” and Ramos Martinez’s “La India del Lago” sold at the Latin American art auction at Sotheby’s last November:

This ceremony that is auction reminds me of the culture of lavish spectacle in 19th century France. The wealthy in the 19th century France went to the theatres not to see but to be seen, and the same seems to apply to the ritual of auction-going today. Thornton hints that people care considerable amount about what they wear to the auction (Thornton 16). As vain as these auctions have become, where they sit in the auction room is terribly important to the bidders because the location of their seats is a “mark of status and a point of pride” (Thornton 16). For buyers, buying is “winning” and the prize won acts as a testament to their wealth and status. For consultants and dealers, buying is an “advertisement for their services” (Thornton 26). There are understood rules in the auction room that are to be followed closely if one did not want to suffer from public embarrassment. This NY Times article spells out these rules: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/05/arts/design/05alle.html?pagewanted=all.

http://www.cartoonstock.com/lowres/vsh0341l.jpg

Another thing I learned is how big of a role an auctioneer plays in the game. Thornton’s account of Christopher Burge was fascinating. I always saw this job as one of the most boring (to which he agrees) and unimportant because all that I ever saw auctioneers do was yell out numbers and banging their gavels. To my great surprise, Thornton reveals that the auctioneer has the “book” that contains all kinds of useful information like the seating chart of all bidders and their bidding behaviors (Thornton 4). I had no idea that the auctioneer knew so much about the bidders beforehand. Using the knowledge he has, an auctioneer can also influence the final price of an object being auctioned off. He is also responsible for picking up signs from the discreet bidders who bid with the slightest gestures (see cartoon). Christopher Burge’s charming, lively disposition, direct eye contact, and calling bidders by their names, all of which can push the bidders to bid higher, can be shown in the YouTube video clip of the auction for Andy Warhol ‘s Soup Can with Can Opener.

According to the Economist, Warhol’s Soup Can with Can Opener was the first of Warhol’s works that were ever shown in a museum and was once owned by the Tremaines (The Economist). So this work has historical significance and desirable provenance. However, another Warhol that had been mostly neglected beat it with a much higher price tag. This hidden card was Warhols 1962 work Men in Her Life, which dealt with “celebrity, wealth, scandal, sex, death, Hollywood, icons of American life” (Artdaily). Its estimate was only available on request, which, according to Thornton, is the case for extremely expensive works. Whereas the Soup Can with Can Opener was sold at $23.8 million, Men in Her Life went as high as $63.4 million. The latter lacks color and was passed from one dealer to another for decades. How can a work like this fetch such a high price? The answer lies with Philippe Ségalot.

Philippe Ségalot, a co-owner of a powerful art consultancy, is an art advisor to some of the richest collectors. When an auction house Phillips de Pury opened a new space on Park Avenue and 57th Street in 2010, Ségalot organized Carte Blanche, a curated auction for which he put together 33 works, including works by Cindy Sherman, Maurizio Cattelan, Robert Morris, Takashi Murakami, and Andy Warhol (Vogel). Ségalot bid against his own assistant and business partner among others and bought the work for the staggering $63.4 million (The Economist). This auction is interesting because one can look at this concept of "curated sales" as either a strategy of an auction house to outshine its rivals or an attempt to select artworks "not for their market value but for their artistic quality," as Ségalot claimed (Artdaily). Whether the fact that Warhol's Men in Her Life beat the Soup Can supports or undermines Ségalot's statement is debatable.

Andy Warhol. Men in Her Life. 1962.http://media.economist.com/images/images-magazine/2010/11/13/BK/20101113_BKP504.jpg

Andy Warhol. Soup Can with Can Opener. 1962.https://encrypted-tbn0.google.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcS6CUfwb5BsG__-Izop6VV_Lpjl_6tvomwYckvdM1HoTnnu-k9t

Works Cited

"A Passion That Knows No Bounds." The Economist - World News, Politics, Economics, Business & Finance. 19 Nov. 2010. Web. 12 Jan. 2012. <http://www.economist.com/node/17551930>.

"Phillips De Pury & Co. to Launch Carte Blanche Auction at New Space on Park Avenue." Artdaily.org - The First Art Newspaper on the Net. Web. 12 Jan. 2012. <http://www.artdaily.org/index.asp?int_sec=2&int_new=41369>.

Thornton, Sarah. "Auction." Seven Days in the Art World. New York: W.W. Norton, 2008. 3-39.

Vogel, Carol. "Phillips De Pury Wants to Make a Big Splash." Rev. of The New York Times. The New York Times. 27 May 2010. Web. 10 Jan. 2012. <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/28/arts/design/28vogel.html>.

The auctioneer, who whose role used to be more like that of a mediocre salesman amidst a slightly distracted audience, is now a trained conductor with the room at his attention. Christie's chief auctioneer, Christopher Burge, exemplifies the profession's evolved role. He has a reputation for being “genuinely charming and having tight control over the room” (Thornton, 5). As Burge explains his selling strategies, one may call to mind the world of sports or gambling before art. Burge discloses that he keeps a book recording the seated positions of the bidders and their bidding styles, whether they are aggressive or looking for a deal (Thornton, 4). He also credits his ability to read bidders body language after years of experience (Thornton, 21). As a result, Burge and other experienced auctioneers, have a good sense of how things will turn out before the auction begins.

The buyers have changed as well. The auction house used to draw informal crowds engaging in some casual window shopping and light socialization. Today's buyer is much more focused. Some see the event as a serious business transaction by which to diversify their investment portfolios. Others are serious collectors constantly looking to acquire new works to keep them at the top of their social circles. Many attend for a combination of both reasons.

Other factors have changed since Christie's opened. The works offered at auction tend to be quite recent. As Thornton notes in her first chapter, primary concern is not for the meaning of the artwork but its unique selling points, which tend to fetishize the earliest traces of the artist's brand or signature style.” (Thornton, 7).

The bidding room itself is has changed from the greyish-green ideal of 18th century gallery interiors to the stark minimal white that is the standard of today (Klonk, 28). Additionally, the condensed arrangement of paintings characteristic of 18th century displays has given way to a focused and separate display of each work (Klonk, 30).

A recent auction at Sothebys was marked by some the typical attributes of the contemporary auction as noted in the Thornton article. Klimt's Litzlberg on the Attersee made $40.4 million, well above the estimated $25 million it was expected to generate [1].

Link to image here: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/03/arts/design/sothebys-art-auction-totals-nearly-200-million.html

Though Sothebys auctioneers likely use the same statistical methods that Burge describes, this is proof that the market is often unpredictable when those with unlimited financial means are involved. The article also points out that sale had more modernist material than recent sales. L'Aubade by Picasso sold for $23 million.

Link to image here: http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/news/artmarketwatch/sothebys-impressionist-and-modern-sale-11-3-11_detail.asp?picnum=5

This resonates with Thornton's observation that serious collectors tend to buy newer works because they want to stay ahead of the curve (Thornton, 13). This may also help explain why, aside from the Klimt painting, the other top grossing sales were from the modernist paintings. Though these modernist paintings aren't exactly new, perhaps this is a compromise between the uncertainty of the primary art market and the desire to have more recent work.

Bibliography:

[1] http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/03/arts/design/sothebys-art-auction-totals-nearly-200-million.html

[3] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=boaFiyICN0w&feature=related

Klonk, Charlotte. Spaces of Experience.

Thornton, Sarah. Seven Days in the Art World.

The word "auction" is derived from the Latin augeō, which means "I increase" or "I augment". '.

The auctioneer is of great importance in auctioning, because not only does he have to sell, but must entertain as well, while psychologically analyzing and influencing the buyers, through hokey language. It has been structured as a celebrity ceremony with just a means to convince people to buy. I picture a bunch of brainwashed rich aristocrats who for not only selfish, but also ignorant reasons have been bamboozled to think that their act of buying an artwork elevates their status. To me the statement made by Sotheby staffer “we don’t deal with artist, just the work, and it’s a good thing too……….” Because they are a pain in the ass, really strikes me as a selfish act from all the people involved in auction and I hoping this is not the same with art dealers, museums and galleries.

“The artist is the most important origin of a work, but the hand through which it passes, are essential to the way in which it accrues value” (10). This quote here means a lot and is directly linked to what we have been reading and discussion over the past few days. It is rather appalling that this will be verbally said. More focus is being pointed in the direction of the buyer than the artist who made it. “The right collector”-who is the right collector? Should there be anything like the right collector? Or is it a business term used at convincing the public that art deserves a rightful owner just because they have money to buy it? If there say all art is priceless, why are they so interested in the financial gains the works are going to bring them? According to Thornton, the consensus on a particular work of art or artist is that the super-rich buy art for social reasons. Taste, she argues, is determined by the vagaries of fashion; 'collecting art has increasingly become like buying clothes.

The financial interest in the auctioning has gone on for so long such that even if people are there to buy art for its sake, the purpose is not realized, because all you will hear are people in whose mind are thinking about how much the work will cost in the next 5 year and the social prestige they will gain from buying it. Having looked at a couple of auction video, I realized that the auctioneer does not utter a word about the content of the work, the meaning behind it and why it was made and for what purpose it was intended for. It is art for Christ’s sake not ordinaryauction sale.

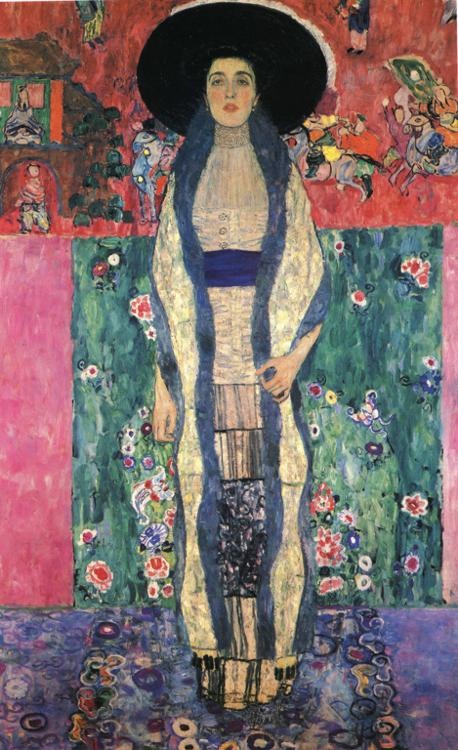

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Baur II (the most expensive painting auctioned in the Christies NY)

Watch the video of the auction__________ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUcCK74HIY0

A 1912 painting by Gustav Klimt, it depicts the wife of wealthy industrialist Ferdinand Bloch-Baur, an avid supporter of the arts and sponsor of Klimt. It was sold at Christie's in November 2006 reaching almost $88 million making it the most expensive painting auctioned in the Christies. The subject of the painting Adele Bloch-Baur is the only model to be painted twice by him.

Christie’s has added and perfected other services other than live auctions. Christie’s also engages in private client-to-client sales between customers outside of the auction room. In addition to this Christie’s has branched into real estate as well.

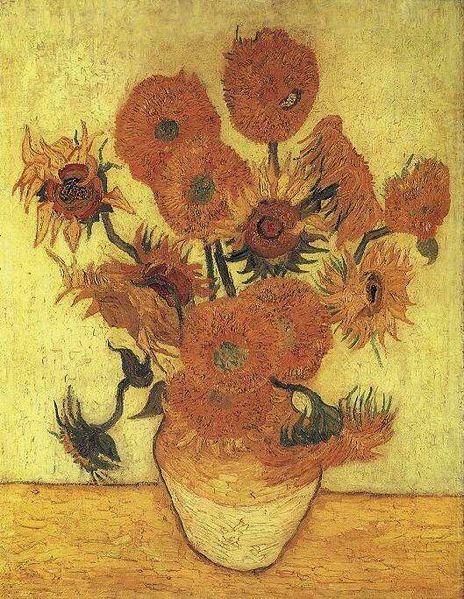

The rise of the Internet helped auction houses thrive in terms of accessibility. Many people, perhaps from foreign countries are now able to participate in European and North American auctions. Christie’s development and growth had a significant impact in parts of Asian and has contributed to the establishment of a viable art market there. During the late 80’s with the growing trend towards globalization many wealthy Japanese people became very interested in Impressionist art, specifically the works of Van Gogh and Monet. This booming international market caused prices to skyrocket. For example, in 1987 the Insurance company “Yasuda Fire & Marine Insurance Company” in Tokyo now known as “Sompo Japan Insurance” purchased Van Gogh’s Sunflower painting for $39.9 million US dollars. This Van Gogh was the most costly painting ever sold at auction. The sale more than tripled the previous record, which was $11.1 million US dollars, paid in 1986 for an Edouard Manet. The transaction shocked the entire art world. This period has come to be known as the Japanese Buyer Boom.

Van Gogh's Sunflowers (1889) purchased by Japanese Insurance Company in 1987.

Just judging from the 'then and now images' of a Christie’s auction I would guess that the original Christie's auction setting would have been quite chaotic and not quite as gentile. In 1810 Christie’s buyers would most likely have been art dealers themselves, looking to buy wholesale with significant retail mark up for their clients. This has changed significantly in the evolution of Christie’s because the new buyer tends to be the private collectors themselves and tends to be new money rather than establishment.

During the early years of auction houses buyers tended to be like a small, central, private clique, whereas today’s buyers come all around the world thanks to Christie's expansion in a catalogue business and globalization.

I do believe that in genreal the sellers have mostly stayed the same. In Christopher Mason’s book The Art of the Steal he refers to the auction house vendor as being precipitated by the three “D’s”: Death, Divorce and Debt. I think this statement was true at the commencement of Christie’s and still rings true today. However, todays sellers can also include museums wanting to de-asses certain works to raise funds or even private collectors wanting to “refurbish” their collections.

Another major changed that has occurred is the social status of the auction. In 1810 Christie’s auction floor looks frantic as the pushy buyers mirror cattle being herded. Today auctions have morphed into entertaining events where people go to be seen. Also, in the early stages of the art market selling a painting was seen with stigma. It was likely assumed that the selling of a painting only resulted in a need for quick cash. Today, many sellers plan to donate the earnings of a sale to philanthropic efforts. One example of this is when David Rockefeller sold his Mark Rothko painting in 2007 $72 million US dollars at a Sotheby’s contemporary art auction. Mr. Rockefeller had owned the painting for 47 years and stated that he would put the paintings proceeds towards charity. Mr. Rockefeller also had a private box to watch the auction from which shows how entertaining an auction could be. The Christie’s live auction has truly evolved since it’s inception and has ultimately become quite an integral part of not only the art market but the global economy.

David Rockefellar's Mark Rothko painting White Center (1957)

Purchased by Rockefeller for $8,500 or $59,000 in today's dollars and sold for $72 million US dollars in 2007.

The actors in the auction do not change from year to year, Thornton notes in her work that many sit in the same seats they had at last year’s auction. It is a small community where auctions are used for more than just buying and selling art, but catching up with friends and seeing rival bidders.

Ultimately, the auctions is less about the art than it is about verifying the current trend or showing the value of a certain brand. The recent Liz Taylor auction shows that auction houses can push prices sky-high by focusing on certain aspects of the art, instead of just the art itself.

Liz Taylor found the Hollywood spotlight in the 1944 movie, National Revolver. Just 12 years old at the time, her role in the movie led her career to achieve superstar status, taking her from child star to movie star. A recent Christies’ auction put up for bid a lilac leather-bound script which was used by Liz Taylor throughout the movie. The auction was expected to being in $2000-$3000, however the bidding went all the way up to $170,500. It is no mystery why the script was sold for so much higher than its expected value- and has everything to do with how the auctions are set up. Fantastically wealthy buyers are placed in a room, essentially competing with each other for a measure of wealth. The script is not the point of value in this sale. Instead, it is the fact that it belonged to Elizabeth Taylor, and further that it marks a certain sophistication and wealth of a buyer. Often auction houses will not sell a piece which has been sold on the primary market within the last two years. This is in order to gain the power of speculation. The works that auction houses sell are not only so that collectors can experience art, but so that they can say they have validated their preferences.

Consider & comment:

Please use this space to respond to your classmates' work and to engage in lively discussions on the day's topic. Keep your comments concise and conversational by responding to others, rebutting or supporting their ideas. Use the comment box below for these observations.

11 Comments

user-1a787

Just a little correction: It's James Christie, not John Christie. Google and Wikipedia tell me that John Christie was an English serial killer....haha.

Cheryl Finley

Dalanda, Nicholas and McKenzie, you've chosen wide range of interesting works from recent auctions -- from the Qing and Ming dynasty porcelain to Van Gogh to Liz Taylor -- and your reading of Thornton through these examples are thought provoking. Dalanda, I was curious to know, considering the work examples you chose, which were of great historical and indeed cultural significance, if authenticity was discussed anywhere in the auction catalogue? Increasingly, when works such as these come up for sale at auctions in the US and elsewhere, questions about the object's cultural heritage and national ownership and/or repatriation come up, as do questions regarding the object's authenticity. Would you care to say something about the issue of authenticity, cultural heritage, national patrimony or repatriation? McKenzie, I enjoyed your close reading of the 1810 aquatint of Christie's Auction room in comparison to the contemporary Christie's as recounted by Thornton and Mason. To be sure, some things have stayed the same, while others are markedly different. There will always be a seller who is looking to make a work of art liquid, and quickly. But the sellers and the buyers have changed over the years. Old money is still there on the buying and selling end, but less present physically, either b/c they're in the booth observing out of site, represented by a dealer in the room, or having someone bid for them by order or electronically. As you note, Christie's advertising tactics, diversified portfolio (including real estate and just about anything under the sun), and globalization has made it possible to avoid the auction room altogether -- unless one wishes to be seen. That is, the internet and other forms of virtual bidding have taken some of the publicity and fan fare out of the auction experience, in my opinion. More frequently today, the preview -- where potential buyers, curators, collectors, dealers and interested people come to see the work on exhibition for inspection prior to the sale -- is the place to be seen, as opposed to the actual live auction. Your example of the Rockefeller Rothko reminds me of the most recent Postwar-Contemporary sale at Christie's in New York, where Peter Norton (of the Norton Antivirus and a huge contemporary art collector) sold a portion of his collection in order to use the proceeds to establish a foundation. Nicholas, your bring up some important points regarding validation (of social status, trends, value) and the unchanging nature of the auction room vis-a-vis its actors (buyers/sellers). As an art appraiser, specializing in photography, who has attended more auctions than she can remember, I can attest to seeing these two attributes in action on a regular basis. In fact, it was part of my job as an appraiser to attend auctions to validate that certain works were selling for certain prices (retaining, gaining or losing value); and that certain collectors, curators or dealers were buying or selling those works. The Liz Taylor example (it's National Velvet, by the way) was a good one and I remember walking by Christie's not too long ago while the collection was being previewed and wishing to go in to see it...Do you think the high price garnered for her copy of National Velvet had more to do with just wealthy Liz Taylor collectors competing for status ("a measure of wealth), and perhaps a little to do with the aura of the object? Good work all!

user-5b6bf

Hi Cheryl -- as the sense I am getting from the contemporary art market is that modern valuations of art are very subjective and qualitative, and dependent on the herd mentality and valuations by peers, I am wondering how the professionals, such as yourself (and not, say, collectors or consumers), arrive at art valuation. Do you arrive at valuations based at what you see is the actual value of the art due to historic transactions and precedents? Do you value it based on the inherent quality of the work? Do you value it based on where you see future demand trends, or what the piece could achieve at auction in say, five years, given current buyer preferences? Or some combination of the three? This is probably the trickiest market I have ever seen in terms of efficient pricing, and I would love to hear the professional methodology. Thanks so much!

Cheryl Finley

Great question, Charles. There are many factors that appraisers takes into account when appraising a work of art. Here are some: historical significance; artist and his/her standing; medium; size (believe it or not!); cultural significance; rarity; subject matter, condition; quality, publication history, exhibition history. Comparable sales at auction and in the retail market are taken into account, based on past recorded sales, conversations with dealers, gallerists and artists, but future demand trends are not part of the equation. You are correct in suggesting that valuation in the art market can be very subjective, but that isn't always the case and the more well known the artist and his or her own record, the less likely that the subjective view of the appraiser will be a factor. Comparable sales are always a useful measure, but the factors mentioned above have to be taken into account, especially subject matter, condition and size. Photography and other multiples often have lots of comparable factors to consider, even for the same or similar example of the same work. Here, often, in the case of multiples, condition is the key determining factor between two works by the same artist of the same subject from the same edition.

user-9c486

On the one hand, I think determining the value of art is very complicated given the numerous factors that play a role.. On the other, Thornton's comment that "art is only worth what someone is willing to pay for it" kind of sums it all up.

user-c6d08

Based on what I saw from the auction catalogue website, I did not find anything suggesting that these pieces were not authentic. In my opinion, I do believe that works of art created during a significant point in a country’s history should go back to that country. These works of art can be thought of as important pieces of a puzzle in a nation’s history. I feel that it is very important to be able to look into what a country believed, how they celebrated, mourned, etc through art. This cannot be done if pieces are sitting in the corner of an abandoned room in someone’s house. This can only be done through repatriation and allowing the country to enjoy the fruits of its loin. Even if it is not in that country per se, I do think that it should be in a museum. I think historical art serves a greater purpose in that it is a learning tool, and one of the few gateways to actually understanding the past.

user-75024

I think that for pieces with certain historical significance you can make the claim that the art should go back to the home country. However, it is a slippery slope. On one hand, you want to respect the nations and regions that the art has come from, but in another, private collectors may value this art for both the work and the history. To a certain extent, all art represents an aspect of a society, region, or historical period. At what significance would a piece need to be returned to the home country? If I am a collector of Bulgarian artifacts because I have an emotional connection to the country, when should my preferences be over-looked in favor of the country's?

user-fd7c0

In Thornton’s chapter, Amy Cappellazzo’s list of factors that determine the desirability/value of a work at auction such as color, feeling (glum v. happy), content, media, and size is fascinating (and reiterated I see in Prof. Finley’s response to Charles).

I was also intrigued by Thornton’s footnote about the disparity in prices between art by male and female artists and the low numbers of female artists whose work has sold for more than $1 million at auction. While Thornton attributes this to the fact that, “the bulk of big-collectors are male,” I wonder: Are there other factors that contribute to this “undervaluation” of art by women and what are they?

Interestingly, in the reading, the buying of art is described by two different men as a “macho” or “alpha male” experience.

Cheryl Finley

Thanks for your thoughtful reply, Dalanda. I agree with you. One often wonders where these works end up, as you put it, in a museum or in the corner of someone's house.

user-75024

One interesting aspect of the auction that I saw throughout many different sales was the difference between the expected value- as appraised by the auction house, and the actual amount paid. It seems to me that auction houses have a preference for beating expectations. If the auctions at a certain house almost definitely beat the expected valuations, sellers may choose one over the other. Also, if a certain artists work beats expectations by a large amount, it drives up the price for future sales for that artist. Prof. Finely, as a professional in art valuations, do you think that auction houses set valuations lower on purpose, or is there just a bias of information showing auctions above expectations and ones which do not meet values aren't as big of news?

user-e58b5

I am also interested in the large discrepancies between the projected prices of certain artworks and the actual prices they brought in. Burge describes all of the painstaking detail that goes into his preparation before each auction- his record keeping, his play-by-play rehearsals, his sessions with trainers and voice coaches. I am wondering if anyone has thoughts as to how much of an influence these factors have on the prices that the auctions are able to generate.

Does anyone have any examples of a less experienced auctioneer affecting sales negatively?