Art dealer Larry Gagosian on the cover of Art Review

DAY 8 Today is Tuesday, January 10th, and we are taking a closer look at the contemporary art market through the

work of Don Thompson (the $12M Stuffed Shark), Robert Hughes' BBC 4 documentary, the Mona Lisa Curse,

and selected high powered art dealers, such as Larry Gagosian. As you consider the assigned readings and film,

choose a contemporary art dealer to report on with regards to their philosophy of working with artists and collectors,

but please don't all choose Larry Gagosian. At the end of the FT interview and throughout the WSJ article several

other high-powered international art dealers are mentioned for you to choose from. You might also consider the

practice of branding and its effect on artists, their work, its value and marketing, and, of course, dealers. Have fun

and remember to include links to videos, images or indices that help to explicate your post!

Readings

Read the following short chapters from Don Thompson's The $12M Stuffed Shark (Palgrave/MacMillan, 2007): Branding and Insecurity; Branded Dealers; the Art of the Dealer; and Art Fairs: the Dealer's Final Frontier. ThompsonChapters.pdf

Read the recent Wall Street Journal article about global art wheeler-dealer Larry Gagosian, "The Larry Gagosian Effect": http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703712504576232791179823226.html

Watch the acclaimed BBC Channel 4 documentary the Mona Lisa Curse, narrated by art critic Robert Hughes, 2008, 75 min. It is available below in twelve six-minute segments:

http://art-for-a-change.com/blog/2009/11/the-mona-lisa-curse.html

Highly Recommended: Read the FT interview with Larry Gagosian and note the list of ten art world gallerists/dealers in competition with Gagosian for the head of the pack: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/c5e9cf78-dd62-11df-beb7-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1Om9FVW97

Individual Contributions

An example of a highly influential art dealer who is considered a key rival of Larry Gagosian is Arne Glimcher, founder of the prestigious Pace Gallery, based in New York City. It represents many contemporary artists and also the estates of notable figures such as Pablo Picasso and Agnes Martin. Glimcher founded the gallery at the age of 22 in 1960 and has grown the enterprise into a worldwide presence. A failed painter, his lifelong obsession with excellence drove him to become a student of art history and connoisseur of its modern commerce. Through a series of calculated risks, Glimcher won the loyalty of several rising artists like Chuck Close, and his business took off, as he eventually became the first dealer responsible for a $1 million sale of a living artist. His emphasis has never been business, however; he has stated that he never entered the profession to become rich, instead focusing on the beauty of art and a desire to become immersed in the art world. While an acknowledged rival of many prestigious art dealers, Glimcher represents a very different philosophy than a dealer like Gagosian, as his emphasis has never rested on maximization of value, gross expansion and the accumulation of wealth and recognition, and the creation of a strong "brand," but instead on the inherent beauty of art the the maximization of the art world in general; he can be seen as a closer parallel to Albert Barnes in this regard. While artists have been "poached" from Pace by Gagosian due to the promise of potentially higher market valuations and return, still other have been poached from Gagosian by Pace, due to the increased levels of loyalty, appreciation, and a focus on the artwork itself that is demonstrated by the Pace gallery.

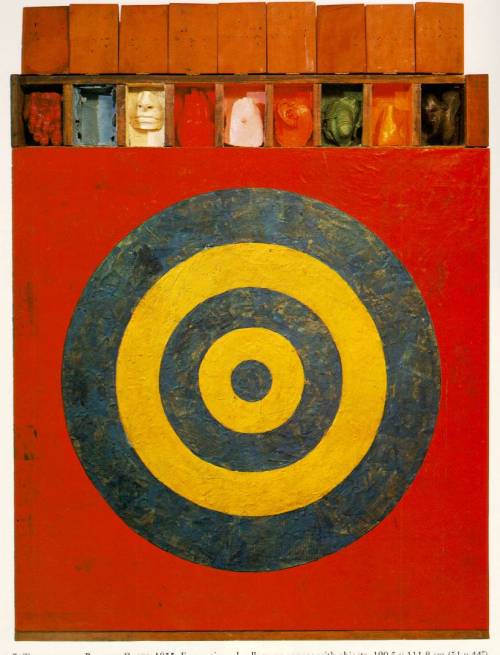

Below is a picture of Three Flags by Jasper Johns, which was the subject of the first $1 million sale of a living artist's work, represented by Glimcher:

Perhaps indicative of the Pace gallery and its artistic connotation, Jasper Johns wrote a letter to Glimcher after the above sale, stating that "one million is a staggering figure, but let's not forget that it has nothing to do with art."

Owner and director of the Mary Boone Gallery since 1977, Mary Boone is an influential contemporary art dealer in New York City. From articles about her, interviews with her, and visits to her gallery space, she seems to be the epitome of the contemporary dealer today. She is well spoken, outgoing, personable, and she never stops promoting her artists and their art.

Mary Boone

In an article in the daily observer she is quoted as saying:

All I can say is, when 1989 hit, I had a very beautiful [Cy] Twombly, an extremely importantBrice Marden painting, and a 1966 Agnes Martin, all of which were losing value by the day," Ms. Boone recalled. "Everyone kept telling me, ‘Sell them! You can at least break even, but I was stubborn and determined not to just break even. I ended up waiting a year and a half and selling them for half. So now, people realize that it’s either you decide to stay in it for 10 years or sell right away.

It is clear from this quote that she prizes money a great deal and even sees it as the end goal in her artistic transactions. Unlike many gallerists who try to stay pure to the cultural significance of the work they sell, Mary Boone is forthright in acknowledging that money is important to the industry and allows her to continue to "help" artists. Boone has a reputation from using the media to her advantage to create a buzz about herself, her artists, and the market in general. She is branded for her role in the 1980s market frenzy, known in the art community as an aggressive dealer looking to make as much money as possible. It is said that at the time she often would "encourage" artists to certain kinds of sellable work or even bully them into showing unfinished work in order to fulfill growing demands from clients. Interestingly, according to more recent interviews, there is a new Mary Boone in town. She has seemingly switched gears after becoming the scapegoat for much of what happened in the market crash of the 1990s. Her rhetoric now focuses on a desire to and joy in helping artists to work at what they love. And instead of an expensive 30 year anniversary soiree, she is planning a new venture called "Young at Art" with 30 schools in 5 boroughs of the NYC school system. Whether she has really turned over a new leaf, or simply realized that her days of aggression need to get buried for PR reasons, one can never be sure. All I can tell you is that this new marketing strategy has indeed worked, and her gallery continues to thrive even in uncertain times. When she was starting out, she sold on the secondary market to keep her new gallery afloat. One of her noted artists says of her transformation:

She’s somebody who never used to be able to hear ‘no,’” Fischl says. “It did not register.” Now, though, “she gets it. She’s changed radically. Dramatically but slowly, if that’s possible. She’s really moved from a mono-focused, obsessive, driven character who could be bullying, infuriating, quick to argue and ultimately isolated to somebody who--through her spiritual development, her revelations--serves her community.

Mary Boon Gallery Space, 2011

She claims in her interview that she has never looked at a slide from a young artist. She exclusively gets tips and introductions from established artists and collectors about emerging artists who she should consider to take on, trusting in the relationships already established between these parties. So even though she claims to be a dealer who is supportive of young, fresh art, it is clear that reputation and branding also play a huge role in her decisions. She says that she is able to rationalize commerce with art by "helping people to have the jobs they want". She works with 20 to 25 artists at a time, and her staff seems loyal to her, which is beneficial to create an atmosphere of trust in artists coming to the gallery. She calls it a "Service - Oriented" space. The artists in her gallery have close relationships, get criticism from each other. Yet it seems clear that many artists sign onto her gallery because of the branding that she has established around her name, and because of the branding that she can bring to their own names. Once an artist is branded, especially by someone as influential in the field as Mary Boone, they can command higher rates, higher prices, offerings to better collectors and institutions. This can mean great things for the sale of their work, but as was the case with Mary in the 80s, it can also cause an extremely high demand meaning lower quality work might escape into the market because of time constraints.

http://www.wmagazine.com/artdesign/2008/11/mary_boone

“it’s very important [for her] to make [her] decisions based on [her] honest feelings about the work. Not to go running after every artist who’s hot for a year. And not to be focused on trying to gather a bunch of famous artists together…[she] promised herself [she] would not be swayed by an artist’s popularity or their money-making abilities […]”

She is clearly a woman governed by the historic importance and cultural value of art---traits very unfamiliar of some other dealers. Very rarely does one see such a dealer, yet her history does corroborate her claims. Goodman interacts with artists she likes, those who will add cultural and historical value to her gallery, and to those artists who help her achieve her goal of teaching the value of art, she is very loyal and faithful. Also unlike many dealers, Goodman never takes on artist when he or she is already a big star or has reached the peak of their status. Instead, she usually takes on “young artists who seem likely to matter” and supports them. She is open to working with young talent and it has enabled her to stay ahead of the curve in the art world. The youth bring fresh, new, ideas that she can help deliver to the art world.

Kerry Brougher, deputy director of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum in Washington says “it’s not enough for her just to sell [art] to a private collection for a great amount of money. The art has to be out there where the public can see it”. She is one dealer who definitely is not solely governed by the revenues accompanied with art sale. At a recent dinner for one of her artists, Goodman dined with curators, artists, critics, and various other cultural figures, but not a single collector. She is more invested in the cultural value of art than in the monetary value. Goodman seems as though she does not force interaction with collectors as some other dealers may. Because she values the art more than money, it seems as though when a collector presents him or herself, she will be willing to oblige, yet she does not furiously pounce at the opportunity to make a sale.

Picture of Marian Goodman:

Practice of Branding:

- You are nobody in contemporary art until you have been branded.

- Branding adds personality, distinctiveness, and value to a product or service. It also offers risk avoidance and trust.

- Successful branding produces brand equity, the price premium you are willing to pay for a branded item over a small generic product.

- A consigner of a valuable Picasso can negotiate the seller’s commission---sometimes to zero; the promotional package, even the identity of the auctioneer.

- New York and London are the two nerve centers of the world market for high-end contemporary art---and they are where branding is most evident and most important. New York and London are themselves brands.

- In the end, the question of “what is judged to be valuable contemporary art” is determined first by major dealers, later by branded auction house, a bit by museum curators who stage special shows, very littler by art critics, and hardly at all by buyers.

- High prices are created by branded dealers promoting particular artists, by a few artists successfully promoting themselves, and by brilliant marketing on the part of the branded auction houses.

- Branded galleries are more intimidating and abrasive. If a dealer recognizes you as not affluent you are treated as an unwelcome intruder or worse, as a fool, and he will patronize you. If you look somewhat affluent and interested, the dealer may follow you around, speaking a form of dealer-code that is confusing and annoying. The galleries are so bare (“white-cube style) and resemble a true elitist space. Mainstream galleries and others lower on the dealer pyramid tend to be less psychologically daunting.

Branding effect on artists:

- Collectors seek out branded artists (could be better for business for the artist) because they become more valuable and their selling power increases significantly.

- Buyers can be reassured that a specific artist is legitimate and thus will award them buy purchasing their works since branding is accompanied by trust.

- For example, Prada offers the reassurance of elegant contemporary fashion and a Mercedes care offers the reassurance of prestige.

- The market tends to accept that artist as legitimate whatever the artist submits.

- Japanese artist On Kawara, creates “one-day paintings” in which he limits himself to the hours of one day to create a work of art. A painting unfinished by midnight is discarded, as it would no longer be a day painting. Kawarau is a brand and has been making such paintings since 1966.

- Artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres has a work of art referred to as Lover Boys, which consists of 355 lbs of individually wrapped blue and white candies. The estimate was $300,000-$400,000 and it sold for $456,000. Even art lovers were bewildered by this work.

- A branded artist such as Jeff Koon’s seems to be able to sell almost anything, and his collectors can have almost any work accepted for resale at an evening auction.

- Artists who have achieved branded status, such as Damien Hurst or Jeff Koon’s, can negotiate lower commissions, the frequency of shows, advances, even payment of a “signing-on bonus” with the dealer. (Greater artist power comes with branding)

Branding effect on their work:

- Collectors visit branded art fairs---more exposure.

- The name and status of the work increases and becomes more well-known and respected.

- Greater likelihood of a successful sale.

- Can become newsworthy and more popular.

Branding effect on the value of their work:

- Collectors bid at branded auction houses---evening sales bring in more money.

- Brand equity has a huge effect on art pricing; there can be high returns made on successful brands.

- An emerging artist’s work that sells for 4,000 Euros at one gallery might sell for 12,000 Euros at a branded gallery.

- In contemporary art, the greatest value-adding component comes from the branded auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s. They connote status, quality, and celebrity bidders with impressive wealth. Their branded identities distinguish these auction houses, and the art they sell from their competitors. As Robert Lacey described it in his book about Sotheby’s, you are bidding for class, for a validation of you taste.

- A work offered in a prestigious evening auction at Christie’s or Sotheby’s will bring on average 20% more than the same work auctioned the following day in a less prestigious day sale. It is “Evening Sale” that adds value.

- Successful branding by artists, dealers, and auction houses produces huge prices for the “stuffed shark” and other contemporary work (including their own work).

Branding effect on marketing:

- Increases the importance of marketing since branding is the end result of the experiences a company creates with its customers and the media over long period of time---and of the clever marketing and public relations that go into creating and reinforcing those experiences.

- Branded dealers have the ability to open foreign galleries and thus approach new artists. This will enable them to widen their collection of artists leading to greater art and greater profits later on. New galleries also offer a place to preview art and artists before presenting them in New York or London.

- However the disadvantage of expansion is that the dealer spends so little time at the home gallery that important artists and collectors become annoyed. For most superstar galleries, the director is the gallery.

Branding effect on dealers:

- Collectors patronize branded dealers, they’ll have an easier time marketing and promoting the works of their artists.

- Branded dealers add value to works sold by them in their branded galleries.

- The dealer brand often becomes a substitute for, and certainly is a reinforcement of, aesthetic judgment.

- Larry Gagosian’s clients can simply substitute his judgment or that of his gallery, for their own and purchase whatever is being shown, even sometimes without seeing the actual painting first.

- Well-known artists gravitate towards superstar dealers, thus creating better business for both parties involved.

- The branded dealers manage the long-term career of a mature artist, placing work with collectors, taking it to art fairs, placing it with dealers in other countries, and working with museums. These dealers are the gatekeepers who permit artists’ access to serious collectors. They represent the established artist whose work brings newsworthy prices at auction.

- Being with a branded dealer allows artists to hang out with with other artist at the top of the food chain. Something that usually doesn’t happen until an artist gains status.

- The branded dealer undertakes a range of marketing activities that include public relations, advertising, exhibitions, and loans. Most marketing is not intended to produce immediate sales but rather to build the dealer brand and obtain coverage for the artist in art publications.

- The prototype for today’s branded dealer was the legendary Joseph Henry Duveen , an Englishman who dominated the trade in selling Old Master paintings to early 20th century American industrialists. Modern dealers emulate Duveen in choosing narrow, upscale target market and selling status as art---although no modern dealer offers sale-without-ownership, or mate selection.

- The key to success of a dealer (and specifically Duveen and Catelli) was the implicit trust that accompanied their brand. The brand gave clients the confidence that neither the artwork nor its price need ever be questioned.

- Some branded/superstar dealers may also publish a catalogue of the artist’s work to accompany an exhibition. The catalogue is intended to document the artist’s progress, and has become so important that artists have switched dealers to protest at the failure to produce a catalogue.

References:

http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2011/11/20/marian-goodman-the-accidental-art-mogul.html

http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2004/02/02/040202fa_fact_schjeldahl

http://www.wmagazine.com/artdesign/2007/11/marian_goodman

Thompson, Donald N. The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. Print.

Videos of The Marian Goodman Gallery:

Gerard Richter at Marian Goodman Gallery-NYC

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8iexVdKzUdk (1)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uzGHOBWMMx8 (2)

Some art at the Gallery:

Maurizio Castellan

Him

2001

Wax,human hair, suit, polyester resin

Gerhard Richter

Lesende

1994

oil on linen

I have chosen to write about Marian Goodman of New York, whose gallery features Gerhard Richter and Jeff Wall. The goal of her first gallery, which opened in in 1977, was to “establish a vital dialogue among artists and institutions working internationally.” Her gallery is all about the front room. Goodman seems to stay away from the business aspects of being an art dealer. She never sells works that her artists haven’t made. She is known for being more concerned about showing art, rather than about selling it. This is unlike Gagosian, who seems to be very caught up in the monetary and hype aspects of the contemporary art market. While she is not the same level of branded dealer that Gagosian is, she definitely has a strong loyalty and integrity with the artists she represents and the clients of her gallery.

Here is a picture of Goodman:

Even though she is almost always referred to as a dealer, she does not like the term and would rather be called a “gallerist,” as she says a “gallerist represents artists, and a dealer represents a work” (Thompson, 29). (Personally, I think that is a marketing technique in and of itself as there is no big difference between the two.) She represents many famous artists who have been featured in top museums, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and MoMA in New York. One art critic called Goodman “the most respected contemporary dealer in New York, for her tastes, standards, and loyalty to her artists. Goodman believes that dealers should commit to working with an artist for 15-20 years. She is very loyal to the artists she works with; she’s been with some of them for 25+ years. I think it is this loyalty that makes her so successful.

She does not seem to be one of the art dealers who frequently loses their artists and her status as a “branded dealer” definitely creates value, what Thompson refers to as “brand equity” (Thompson 13). Branding for the artist and the dealer is key with contemporary art – not only for the dealer and the artist, but just as important for the customer who gets a “validation” of taste, “class,” and “reinforcement of aesthetic judgment.” (Thompson, 14). With contemporary art, where there is “no standard formula for determining what an artist is worth,” having a branded dealer who can “set the market” is key (Crow, 4).

Given the enormous power these dealers have, I wonder if there needs to be some kind of legal regulations put in place in the art market, such as a limit on the dealer’s commission. It would be hard to do. But even if it could be done, it may actually hurt the market. It’s hard to say if regulating dealers is a good or bad thing.

What do you think?

Goodman currently has a gallery in New York City and Paris. Here is the link to the gallery’s website:

Here are links to newspaper articles written about her:

http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2011/11/20/marian-goodman-the-accidental-art-mogul.html

http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2004/02/02/040202fa_fact_schjeldahl?currentPage=all

http://www.wmagazine.com/artdesign/2007/11/marian_goodman

Here is a video of the Gerhard Richter exhibit at her gallery in New York:

Another important art dealer other than Gagosian is Barbara Gladstone (born in 1935), an American who has been in the business for over thirty years (photo below by Andrea Spotorno). Her eponymous galleries are located in the Chelsea district of New York City and described as being among the largest in the area. She also has a fairly new gallery in Brussels, Belgium. Gladstone represents many popular artists such as Shirin Neshat, Sarah Lucas, Matthew Barney, Anish Kapoor, Carroll Dunham, and formerly Richard Prince (who she lost to none other than Gagosian in 2008). Through these artists, Gladstone Gallery represents a wide variety of contemporary art from installations and conceptual art to paintings, photography, film, and sculpture.

At forty years old, Gladstone left Hofstra University where she taught art history to open a gallery in Manhattan. In a Wall Street Journal article, Gladstone is described as having strong ethics, and much like the dealers interviewed in Velthius’s book, Talking Prices, claims that, "This isn't like selling real estate or stock. We deal in personal relationships,” and compares her relationships with artists and collectors to that of a family. At the same time that she purportedly only cares about her role as “mother” to artists through helping them develop and reach their potential and represent their art, Gladstone praises fellow dealer Mary Boone for being, “…ambitious and determined, as interested in business and having power, and admitting it, as men.” Below are examples of pieces from artists represented by Gladstone Gallery:

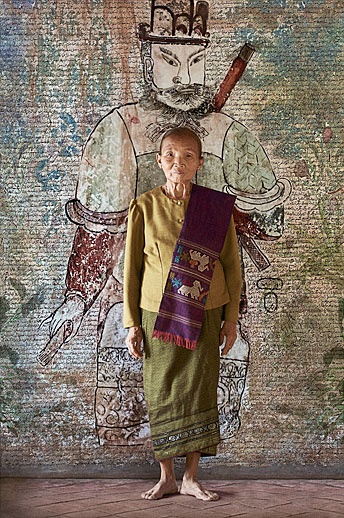

Shirin Neshat's Games of Desire: Solo, 2009 - C-print (diptych) with ink

|

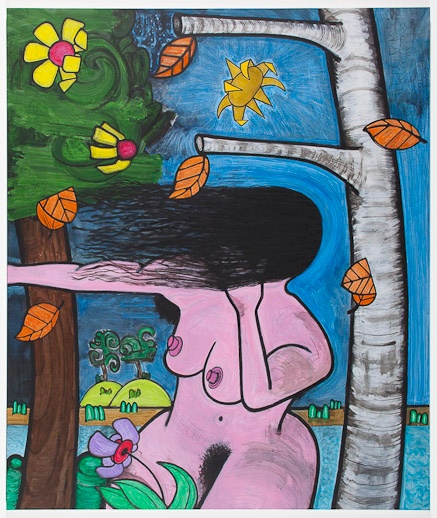

Carroll Dunham's Bathers 5 (the wind), 2010-2011 - Mixed media on linen

Wirth chose London as his hub in hopes of bringing together America, Europe and Asia (Burns). He has turned Hauser & Wirth into a “global brand” that offers exhibitions in its contemporary art galleries in Zurich, London, and New York (Burns). He says that he sees his role as someone who opens up new doors and makes things possible for the artists (Milliard). Another purported role of the gallery is to educate through a “constant dialogue with the public” and loans (Milliard). A lot of school classes come to his gallery, and Wirth has given tours to schools himself on several occasions (Milliard).

Hauser & Wirth also borrows the power of the Internet. Wirth maintains that, while it is useful for attracting people’s attention and making them want to visit the actual gallery, it will never replace the one-to-one relationship, which he emphasizes (Milliard).

Because artists and collectors rarely go to Zurich, unlike many major art cities, Wirth faces another challenge of having to lure them into Switzerland, which he says he does by having a story to tell and telling it compellingly (Wullschlager). The result of this story is reflected in his success in art dealing.

According to Artinfo UK, another one of Wirst’s business tactics is to maintain a family business charm, which became possible through his marriage to Manuela Hauser, the Hauser in Hauswer & Wirth (Wullschlager). He works closely with his mother-in-law Ursula Hauser, a collector of modern art (Wullschlager). Because the art market is a vertical market, a lot of it is, in Wirth’s words, a “people business” (Wullschlager).

He claims that, rather than running his gallery like a shop, he tries to act as a bridge between the actors involved in the market, among which are curators, museums, artists, and collectors (Milliard). During his interview with FT, however, he openly admitted to fully taking advantage of the art market’s “system [that]works with tools that would be illegal in any other market – fixing prices, having a cartel” (Wullschlager). I got an impression that it’s almost inevitable that dealers are more entrepreneurs than art lovers.

Realizing that the old gallery model of simple buying and selling was outdated, Wirth provides his artists with production teams, technical crew, studios and storage to facilitate the artists’ production (Wullschlager). He has never lost any of his artists ever since he became a dealer, and I think that winning the hearts of the artists that he picks is essential to his success as someone who has to work very closely with them.

He also admits that there is a lot more “rubbish” flooding the market than couple decades ago but doesn’t seem to be bothered too much by it. He uses this fact to emphasize the role of an advisor (Wullschlager). Talking about contemporary art becoming a “lifestyle,” he says, “There are worse things you can do with your money than buy art. You’re not harming the environment. You’re not hurting other people” (Wullschlager). What he doesn’t seem to see, or doesn’t show, is that this almost nonsensical frenzy of art collecting for wrong reasons that is so common in the art world today is hurting not the environment or other people, I know, but art.

An art critic for several decades, Robert Hughes tells a grim yet compelling story about the contemporary art market in The Mona Lisa Curse. He traces the beginning of what he calls the “Mona Lisa curse” back to the painting’s arrival in the United States in 1962 for temporary loan. His premonition came true when people all made a pilgrimage to the famous masterpiece, “…not to see it but to have seen it” (Hughes). According to Hughes, the commodification of art in the U.S. started here. People saw art not as art but as just another commodity to consume. Some started collecting art as an investment, which developed into today’s art market.

The Mona Lisa suffered and still suffers from what Hughes calls “uncomprehended adoration” by the mass. In the contemporary art market, this “uncomprehended adoration” is deliberately induced and manipulated for financial profit. Although there are still some people like the MET’s director that see dealers and collectors as “guardians” of art (or at least think that they ought to be) because works of art cannot defend themselves and are ‘physically as well as conceptually vulnerable,’ Hughes grumbles at that today’s art world is filled with people who resemble “gamblers” rather than “guardians” (Hughes). Hughes’ grief at the current state of the market and concern for its future are heartfelt.

Iwan Wirth

https://encrypted-tbn1.google.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcTnuP-EFabLWwOgU_n9kAjaMqiSqzkB9mogN_eawP72ghgfpkHA \\

Works Cited

Burns, Charlotte. “Collecting is like a disease- you can only stop when you die.” Latin American Art Journal. 13 Apr. 2010. Web. 11 Jan. 2012. <http://latinartjournal.com/collecting-is-like-a-disease-you-can-only-stop-when-you-die/>.

Milliard, Coline. ""There Is No Place Like London": Dealer Iwan Wirth on the Intricacies of the World's Second Biggest Art Market." Artinfo. 22 Nov. 2011. Web. 11 Jan. 2012. <http://www.artinfo.com/news/story/750832/there-is-no-place-like-london-dealer-iwan-wirth-on-the-intricacies-of-the-worlds-second-biggest-art-market>.

Mona Lisa Curse. Dir. Mandy Chang. Perf. Robert Hughes. Oxford Film & Television, 2008. YouTube, 18 Nov. 2011. Web. 10 Jan. 2012. <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H3ZsoabMXrI>.

Wullschlager, Jackie. “Lunch with the FT: Wirth’s Fortune.” Financial Times. 30 Sep. 2005. Web. 11 Jan. 2012. < http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/335357bc-2fc8-11da-8b51-00000e2511c8.html#axzz1jGhO4wuw>.

Jay Jopling was a visionary art dealer who established his White Cube gallery in London in 1993. He helped to launch the careers of some important young British artists, including Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Andreas Gursky, Gilbert & George, and Anthony Gormley. He was the only British dealer to rival the dominant American art scene with his group of brand name artists.

Though Jopling's approach is more risky and experimental than that of other dealers, he has secured a solid base for his gallery thorough his branded artists. Hirst is perhaps the most well known of these. His works, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living , better known as the $12 Million Stuffed Shark, and For the Love of God, a human skull encrusted in diamonds, are some of the most ostentatious works ever created in terms of price. Because Hirst is such a powerful brand name, he will likely continue to be valued in the art market regardless of the artistic merit of his works. Collectors have already shown their faith in his brand equity, the fact that they are willing to pay more for his name.

As a side note I would like to point out that Hirst's For the Love of God never sold and in 2008 was purchased by a consortium that included Joplin and his gallery. Does this work represent the limit of brand equity? Is it the price that prevented this work from selling or was it something else?

Please see link for image:

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/13/arts/design/13skul.html

Jopling's approach is quite adventurous and he has taken profitable risks over his career. He offered to finance some of Hirst's early works, before he had made any name for himself. He announced on British TV that he would sell drawings that Tracey Emin drew of herself masturbating (Thompson, 37). But Jopling continued to take risks even after securing these well established names. This is reflected in his gallery's business structure, which is fairly fluid in its relationship with artists. He works with about twenty artists total, but does not have a contract with any of them; they are free agents and White Cube is their primary dealer in the UK. In fact, these artists are not shown at regular intervals, as seventy percent of White Cube's shows are dedicated to overseas artists being considered for representation by the gallery (Thompson, 38). This is quite progressive in comparison to other galleries who normally only dedicate five to ten percent of their time to trial shows (Thompon, 38). This is actually an ingenious marketing strategy on Jopling's part.

Jopling has built a brand name for himself and White Cube through the success of the brand names he represents. If branding minimizes collectors insecurity, then Jopling is triply reinforced through the brands of his artists, his gallery, and himself. However, one should remain wary of such pervasive branding, which often replaces aesthetic judgment. As pointed out in the Mona Lisa Curse, the art market has “transformed the museum into a commercial model.” Is the same thing happening to avant-garde galleries?

Bibliography:

Thompson, Don. The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art. Aurum Press, Ltd. London, 2008.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703712504576232791179823226.html

http://art-for-a-change.com/blog/2009/11/the-mona-lisa-curse.html

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/c5e9cf78-dd62-11df-beb7-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1Om9FVW97

With this being said, many dealers have taken advantage of their position in this branding art market, and thus have used the art market solely for monetary purposes, rather than to introduce to the market, new artists and pieces that are unique, but may not sell as well. One of the dealers that has not altered based on his branding was David Zwirner, who owns a gallery in Chelsea in New York City.

David Zwirner has helped artists such as Luc Tuymans, and Neo Rauch to begin their careers, and also represents international artists such as Michael Borremans, Raoul De Keyser, Stan Douglas, Marcel Dzama, On Kawara, Toba Khedoori, Jockum Nordström, Raymond Pettibon, Thomas Ruff, Katy Schimert, Yutaka Sone, Diana Thater, and Christopher Williams. Zwirner focuses on pieces that are historically relevant, while also prompting viewers to feel something through the art. He states in an interview by WSJ Magazine: "When I look at an artist for the first time, the initial reaction I’m hoping for can be anything from discomfort to puzzlement. I go up to any artwork with a huge storage of information that I’ve accumulated over the years, and if I can’t file it or it makes me angry, I think, “Interesting.”"

Zwirner also dislikes the industries manner of being stereotyped as haughty and intimidating, and believes that art fairs are overvalued. He believes that art is for everyone, and that galleries are the entry point for collectors, not art fairs. One of his major problems with the art market is how Auction houses will buy a piece of work from an artist at a relatively low cost, and then turn around and sell it for an exorbanant amount of money, with none of this income going back to the artist. He believe that there should be a 25-year mortorium on selling living artists' work at auction so that the artists can worry less about how much the next piece they create will make them, and more on the actual creativity of the piece itself. I believe that although David Zwirner is now a brand that consumers trust and rely on to purchase contemporary art pieces, he is also very loyal to his artists, and is trying to help the art market, rather than just himself, and for this I believe he is a successful dealer.

[http://www.davidzwirner.com/]

David Zwirner Gallery:

.

It’s our time to tell our history of art and this is how we want to tell it. In all of this dealer, gallery and artist issue, I think a major causative factor for why art world is acting this way is our current society. The current society has grown to show love and respect to money so much so that, moral, traditions and culture is now less valued. As humans we turn to embed ourselves to societal norms and this is the new norm. Having less appreciation for the content of an artwork and focusing on the brand. In this modern era, if so much monetary value is being placed on an artwork, then, it is very important, our generation holds it as historical, that is our story and that is how we will tell it.At least in this case and instance we are using works by current artist, so we are not going about demising the meaning and content behind their works, as opposed to the Barnes Foundation issue. What we might be doing wrong is re-writing art and what it is all about. Now as an artist, who needs money, if I get an art dealer who wants to put me out there and sell my work, I will agree. From time in memorial, the art market has always been competitive, weather it was who painted the most work, who was the greatest artist, who got the commission and now it is who is making the money. Robert Hughes only hurt is that art is not what it was back in his time. He talks about how contemporary art has lost meaning in what art is all about and picks on famous artist whose works cost millions. He talks about the fact that he doesn’t like Andy Warhol’s works and doesn’t understand why it costs so much, he is just the minority few who doesn’t like it, I don’t really like Andy Warhol’s work, but doesn’t mean that other people shouldn’t like it. He also says something very interesting that what happened to the time when people will look at art without asking how much it cost, well is it not rather interesting that people now not only look at art, but through its appreciation, we add value to it too. “Sometimes we don't know if the stuff we're buying is historically significant, but because the prices are so high, we need to believe they're important," said Dallas collector Howard Rachofsky, a Gagosian client.

Bruno Bischofberger

Bruno Bischofberger, known for bringing American pop art, and Neo-expressionism to Europe is an art dealer and gallerist from Zurich, Switzerland. To many people, he is the Gagosian of Europe. He expanded the use of big money in the European contemporary art market. He owns the Bischofberger gallery and also co-founded Interview Magazine with Andy Warhol in 1969 and commissioned the “Collaboration Paintings” with Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat. In 1965 he held an exhibition of American pop artists including: AndyWarhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Tom Wesselmann and Claes Oldenburg. The following year Bischofberger was the first gallery to show the work of Gerhard Richter outside Germany. In 1968 he entered into a “first right of refusal” contract with Andy Warhol, which lasted until the artists death in 1987. Bischofberger introduced Warhol’s work to collectors Philippe Niarchos and Peter Brant, whom he had met as teenagers in St Moritz. In 1969, Bischofberger and Brant became the founding financial backers of Interview Magazine, started by Andy Warhol, and in 1970 produced Warhol's movie “L‘Amour“. Bischofberger became Basquiat's dealer for Europe, and was his most consistent dealer and source of money from then until 1987.It was Mr, Bischofberger who introduced Basquiat to Warhol and played a major role in the Basquiat movie.

last exhibition of the Galerie Bruno Bischofberger in 2011, Zurich

Branding is a way to identify and distinguish yourself from the many other artists, dealer, and galleries out there; a form of recognition and a sign of power to those who hold s true to it. All visionary creators throughout time who have made their mark on humanity are brands. Branding helps to connect your art deeply with your truth, creating a mark so authentic and profound it embodies a timeless power. When you brand yourself as an artist, you release the secret to your personal niche markets. It forms as a core stronghold in Introducing your vision to individual art collectors around the world through targeted marketing techniques. As an upcoming artist I am looking to have my own brand, that way I can be recognized easily due to consistent way of executing my works.

Bruno Bischofberger and his american crew- Warhol, Basquiat,Clemete in New York-1984

David Zwirner's gallery is active in both the primary and secondary markets. Since 1993, it has been home to innovative, singular, and pioneering exhibitions across a variety of media and genres. The gallery has helped the careers of some of the most influential contemporary artists, including Luc Tuymans and Neo Rauch, who had their U.S. debut exhibitions at the gallery. The gallery relocated from SoHo to West 19th Street in Chelsea in 2002, and expanded from 10,000 to 30,000 square feet in 2006, which now allows for multiple full-scale exhibitions.

I found David Zwirner an interesting dealer because he focuses on historically relevant work by a diverse group of artists. In the primary sector, the gallery covers a broad spectrum of contemporary artistic practice, from seminal Minimalist works to large-scale installation (i.e. Dan Flavin) and time-based performances and video work. In the secondary market, the gallery has become known for presenting historically-researched exhibitions and publications devoted to the work of modern and contemporary artists as well.

In an Interview in Wall-Street Journal in 2009 Zwirner said “Art should be the most democratic of all endeavors, but these days it’s not*. *You see cartoons in the New Yorker and stereotypes on soap operas where the galleries are filled with haughty people standing around. It bugs me tremendously that the white-cube gallery is this intimidating, turnoff-ish kind of environment. My front-desk people are instructed to be particularly friendly. You can test us on that and let me know.” Although Zwirner may believe his gallery is more "friendly" than most, I have been to both the Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea and two of Larry Gagosian's galleries in Manhattan and they all give off a snooty and uptight vibe.

Zwirner has been known to host a diverse group of artists, innovative artists and people who push the boundaries of art further. There is no one aesthetic to the gallery, which he prides himself in. Zwirner boasted in the WSJ article "We have Lisa Yuskavage and On Kawara – that’s quite a stretch." Both these artists are highly regarded with strong audiences, but aesthetically they are very different. I personally believe that this tactic of having an array of different artists is a good one as it gives the gallery a more invigorating reputation and is more interesting to the potential clients.

David Zwirner in the David Zwirner Gallery in Chelsea, New York, 2009.

David Zwirner is often compared to Larry Gagosian as a competing leading dealer of contemporary art in New York; however, as dealers they actually have quite different methods. Both but on extraordinary shows, however from what I understand Zwirner comes from the primary market and expanded into the secondary market and Larry Gagosian did it the other way around. Zwirner has a more stable group of artists who he has built up over time whereas Larry Gagosian has tended to grab artists at the peak of their fame and capitalize off them. Although Zwirner, like Gagosian, has a hard-ball reputation, I believe Zwirner is a less "money-grubbing" kind of dealer, unlike Gagosian he is more willing to build relationships with artists and seems genuinely intrigued by each exhibition and show he puts on.

Click here to read the very interiguing interview with David Swirner & the Wall Street Journal: http://magazine.wsj.com/hunter/rebel-yell/arts-go-to-gallerist/

(David Swirner Gallery in Chelsea)

Dealers such as the famous Marian Goodman dislike being referred to as dealers as it implies that they are buying and selling commodities and actually representing a piece of art work instead of the artist themselves. The modern dealer needs to create an environment of attention on the artist they represent and their work. Many dealers are fantastic salesmen/women and are known for not only vying for top dollar in primary market sales, but ensuring that the secondary market pushed the value for artists’ works as well.

Leo Castelli is a perfect example of the attitude dealers must have toward art integrity, yet posses the seller’s mentality for making money and getting big sales. Castelli transitioned from banking to art dealing in 1957. He had a constant supply of paintings from the artists he commissioned, and eased their worry about sales with his idea of paying artists a stipend while they were working on pieces. While Castelli treated his artists well, he also knew the art of the sale. Williem de Kooning said, “That son of a bitch, you could give him two beer cans and he could sell them” showing Castelli’s passion for sales was on par with his passion for art. (These beer cans were later an inspiration for Jasper Johns- seen below).

While Castelli’s skills as a dealer were top notch, one aspect of his business which sets him apart from many of his contemporaries is his respect of artist integrity. When Castelli showed Alfred Barr, the director at the time of the Museum of Modern Art, Jasper Johns’ Target with Plaster Casts (below), Barr asked Castelli if he could change the art to hide the plaster cast. However, Castelli believed in full artist integrity and stated that was not possible and instead, Castelli himself purchased the piece instead. (This was an especially good move as it is currently valued at over $100 million)

Personally, I can see a great overlap between the finance world and the art dealer. Both deal with people’s livelihoods and emotions, however often the best of both professions act with a financially savvy head, but a respect for the integrity of the product and customer. The best dealers focus on the art and the emotion to the customer. The art of the deal isn’t on the value of a painting because one could not put a price tag on emotions. Instead, the best dealers weave art and commerce tastefully – holding the respect of the artist and the customer.

Some questions I have are regarding the regulation of the system. In nearly every one of the assigned readings and the movie, the phrase “unregulated market” came up. What would people want to accomplish by regulating this market? Also are the current conditions of increased mercantilism a permanent fixture in our culture?

Consider & comment:

Please use this space to respond to your classmates' work and to engage in lively discussions on the day's topic. Keep your comments concise and conversational by responding to others, rebutting or supporting their ideas. Use the comment box below for these observations.

12 Comments

user-e58b5

-

user-c6d08

Something I found interesting were these questions posed by Robert Hughes, an art critic:

“What is good art? What use is art, what does it do? Is what it does actually worth doing?---and an art which is completely monetized in the way that it’s getting these days, is going to have to answer these questions or it is going to die”

What do you think? Sometimes I wonder what contemporary art gives to the people of today. Historical art enables us to gauge into the past and art today will allow those in the future to do the same. But I do wonder what it’s explicit value is to the average person.

user-9c486

I think when it comes to contemporary art, it's really hard to set a value to the average person or most any person. It seems that's why branded dealers, like Gagosian, have "enormous power to influence and even set the markets for the artists they represent" (Crow, 4, WSJ). The difficulty in determining worth is exactly why the superstar dealers are so important to the contemporary art market. It looks like the dealers basically have defined what is good art and what is it worth.

user-11970

I mean Dalanda, I think it is a new era in the art world, by branding and setting high monetary value on the artworks, i dont think we are degrading art, i think we have found a new way of appreciating our art. Robert Hughes thinks that because he is not a fun of an artist, then the public or dealers shouldn't place a high mark on it. He is also worried that people look at art and wonder how much it is going to cost, well why not. Making art is also a means of making income, and it has been so from time in memorial.No one wants to be a starving artist. Regardless of the new turn in the history of art, one thing has remained, and that is "Art is still Appreciated" and that is what I believe matters.

user-fd7c0

Kwame, I have to disagree with you as to whether branding and high prices for art are degrading it, I think that they are in some ways. Many people are much more concerned about the "brand" of a work and what it signals about them as the buyer than about the art itself. In fact, some buyers have no real knowledge or appreciation for good art and simply have advisers pick works out for them. Of course artists want to make a decent living and they should but the prices are so high that purchasing (and enjoying) art has become unattainable for most people, should it be this way? While I agree that art is still appreciated for its content and quality by some, by others it is only "appreciated" for its monetary value which I think does a disservice to art and society and can hardly be called true appreciation for art.

user-75024

I believe it was in Thompson's piece in which he states that the new market for art has become so sophisticated, and the sales are fulled with such snobbery, that the collector HAS to use the monetary value to explain purchases and the art's value. Consider Barnes- he was so badly hurt when his collection was criticized that he vowed never to let it in the critics' hands. People are incredibly sensitive about how others view their connection to art and emotion. For many of these people- a price tag and notoriety are the ways which they can ease their cognitive dissonance.

I tend to agree with Elena that the high prices and the branding degrade the art within society. Art is loaned to museums to increase the value, and people with no art background buy pieces in auction houses to say they own a famous work, not so that they can connect with the art more intimately. "Good Art" is now in the eye of the beholder. It is not the education of the artist, nor the time spent on completing a painting, but what feeling and emotion can be derived from the piece. Validating one's feelings on art has transitioned from art critics, to art auctions.

user-11970

let me ask one more question, in the "Art of the steal", it was mentioned a couple of times that the Barnes collection was worth billions, what is your take on that because in this instance, they are placing a price tag on the collection.

Nicholas, are you suggesting that if artworks weren't priced high, then it will not be degrading?, because i am thinking that the higher the price the more it is appreciated.

user-e58b5

Dalanda, I also found that Hughes quote to be very powerful and I wonder what good art is for, what use it is in contemporary culture, and how the average person evaluates it.

Watching the movie I shared Hughes' heartbreak at his answer- that art is now commodity.

But I think that re-framing the question can also be useful. I think that art has always been a mirror to culture, and so perhaps art is not the problem, it is simply reflecting our culture of commodity, which like the art market, has gone to extremes. I think that an artist can choose to work within (like Warhol and Hirst) or against this system. And I think that the average person will fall to one side or the other of this argument, as their worldview probably determines their criteria for value.

user-9caf1

As an artist, this is an extremely emotional, controversial, and honestly frustrating topic to try and comprehend. I want, of course, to be able to make a living (and making a good living is even better). I feel that I can argue that making a decent amount of money from my art will allow me to be able to focus on my work and its content to the exclusion of other time-consuming activities, like having to also work full time. This extra time, will enable me to make better art! And in this way I will be able to contribute positively to culture through the value of my work. This would lead me to the conclusion that branding by whoever markets me and high prices do not degrade the work.

In this argument I am ignoring the reasons for which people are buying my work, and I am also ignoring the culture that surrounds the selling and reselling of the work. The work still exists, just as I made it. I name the "value" of the work to be a quality of the work which denotes its importance to culture (its symbolic, cultural value, and not the money it brings in).

In this scenario, what do you guys think? ... I mean, is the value of the art as I have put it forth then still degraded by the hapless speculation of rich moduls?

user-11970

i agree with you christina, plus the thing is that the people whose works are being high-priced are still alive or were alive when this was going on at least most of them, and they were not in disagreement with it.

user-1a787

As sad as it may look in many people's eyes, I don't think that money can ever be severed from art, if art is to survive, as it should. I agree with you that artists need money and more money can often times result in better art. And like you said, regardless of the price arbitrarily put on your artwork, your work remains as you made it and its aesthetic value does not change. However, I think that its cultural importance actually can be affected by the price tag, which complicates the relationship between money and art. An artwork's price can and does change the way it is viewed and accepted perhaps not by "true/pure" artists but by the majority of the public. As in the case of the Mona Lisa, high prices and the "uncomprehended adoration" that follows can often fetishize and thus degrade art. Also, do you not see it as problematic that works that do not have much artistic merit are being exalted and priced so high as to claim their superiority over the works that are not as expensive? I'm bothered by it. But then again, since I believe that art can't be separated from money, I'm troubled by the whole issue of price degrading art. If an artwork is priced too high, it's bad. If it's priced too low, it's also bad.. This is really a difficult question to answer.

Cheryl Finley

Hi all -- you've done a smash up job with your provocative contributions on the world's top art dealers. I think it's worth noting that they all deal in contemporary art and most have spaces in Chelsea. But with that said, the conversation that's been going on about the crassness of money, or put another way, the high prices paid for contemporary art, I find the question of degradation to be intriguing and I'd like to hear more about your point of view on that, Elena and Nicholas. I also find the distaste of branding to be curious. Even Renaissance era artists participated in a bit of branding if you can remember back to the Patron's Payoff. Great work all, but, I agree, complicated emotionally speaking, for some practicing artists. I thought one of you might have mentioned Damien Hirst....